Applied Science for early-stage founders

Preface: This is not a new planning system, nor a founder playbook. There’s no shortage of great tactical frameworks out there. The aim here is narrower and upstream: to name the epistemic standard that determines whether any system (OKRs, sprints, chapters, Linear workflows) is producing truth, or merely producing motion.

In other words: how do you know you’re learning, rather than getting better at narrating what you’re already doing?

Early-stage companies don’t fail from lack of effort. They fail from undisciplined belief. When feedback is weak, the mind fills in the gaps with stories to keep the body moving. If you don’t build a mechanism that forces reality to speak, you end up mistaking motion for progress.

Rated taught me a valuable lesson across every era of the journey: time in business is not neutral. It either works for you, or against you. It either compounds your decisions, or compounds your mistakes. It is a loaded revolver, and if you’re not holding it, you’re sitting in front of it. There is no version of reality where the gun isn’t there. There’s no “neutral” state for time.

As first-time founders, we often told ourselves we were being rigorous. We stayed on a default path while waiting for more data before making the hard call, commit harder, or pivot. “Just one more month of data, bro, I promise.” Weeks would often became months, and the company, while still moving, softened at the edges. Decision drift did quiet damage, the kind you only recognize later unless you’ve learned to notice it early.

Somewhere in the messy middle, after the initial adrenaline, and before anything felt inevitable, I internalized the real job description. Ken Griffin has a blunt line that captures it well:

“You’re constantly making decisions under uncertainty. That is the job.”

Once you see that, you can’t unsee it. The founder’s calendar is not a schedule of work. It’s a schedule of decisions. If you don’t force decisions, you don’t get clarity; you get narrative. And narratives, particularly the ones that do not match with reality, are corrosive.

Around that period, I started—slowly, then more deliberately—treating early-stage as applied science. I began using decisions as the pacemaker by flipping the relationship between time and decision-making. Instead of letting time pass in the hope that more data would eventually make the decision easier, I made the decision itself the unit of time.

Concretely, that means organizing the operating rhythm of the company around decision intervals. Every two weeks, a decision is due. The checkpoints go on the calendar and recur. That constraint forces compression: you plan and execute inside the interval in a way that produces high-density evidence for the decision at the gate.

The goal is to put yourself and your team in a position to make good decisions at a steady clip, and fast enough to earn survival before you run out of money. There’s an adjacent point here about why over-raising before PMF can dull this muscle, but that’s a separate note.

Done well, it forces focus, cuts scope creep, and improves sleep because uncertainty gets a clock. You stop waiting for clarity. You set a decision date, then do the work that earns it.

This post is the operating system behind that approach.

A founder-friendly definition of “Applied Science”

For founders, “science” isn’t lab gear. It’s a method for staying honest when the signal is noisy.

In early-stage work, the most common failure mode is subconscious: you start using motion as evidence, and “we built it” as “we learned something.” Applied Science is the reverse. It asks for three things before you begin:

You name the belief you’re trying to validate.

You define the instruments that will collect reality.

You define stopping rules that make “keep going” earn its keep.

Nothing in this operating system is invented from scratch. This system borrows heavily from Lean Startup’s experimental posture and Shape Up’s timeboxed execution, but is different in a couple key vectors that make it particularly effective in an early-stage environment.

The “Lean Startup” is an experimentation mindset: it teaches you to treat ideas as hypotheses, get out of the building, and iterate through build–measure–learn cycles, while minimizing waste. What it doesn’t give you is enforcement. It’s easy to “keep learning” forever, while avoiding the moment where uncertainty has to collapse into a decision.

“Shape Up” is an execution container: it timeboxes work, forces scope discipline, and creates space for teams to ship coherent products without endless backlog churn. What it doesn’t give you is a pathfinding grammar. It’s excellent when you already have a direction and you want to ship coherent work; it’s less explicit about how to design experiments, what constitutes disconfirming evidence, and when the right move is to kill the direction rather than re-scope the work.

The “Applied Science” approach borrows from both, but it’s aimed at a different failure mode: decision drift under weak feedback. It makes the decision cadence explicit. You schedule the decision threshold first, then build the instruments that force reality to answer before the deadline, with Kill Gates set up front.

It’s a hybrid of Lean and Shape Up, with one deliberate upgrade: the cycle doesn’t end in a retrospective or a backlog refresh. It ends in a decision, made against criteria you defined ex-ante.

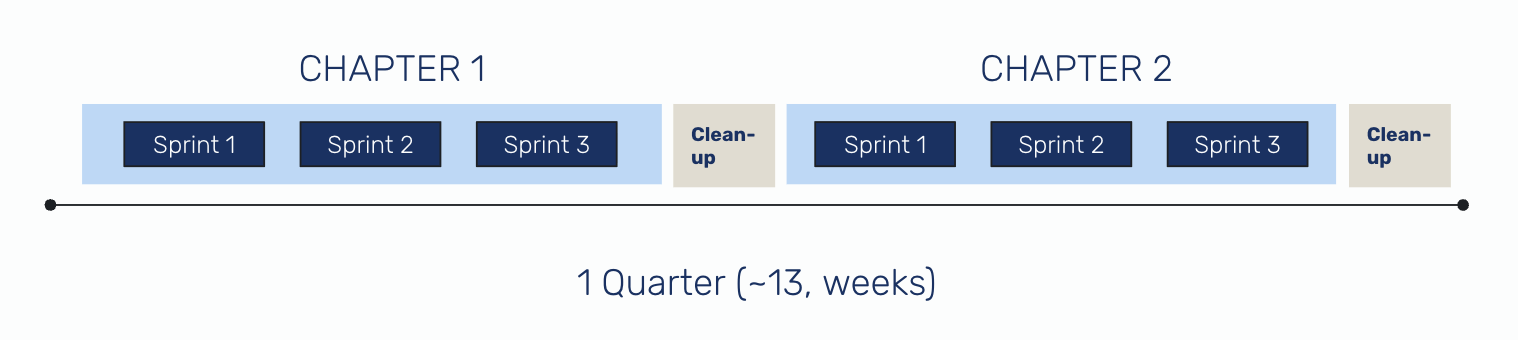

A quarter split in Chapters and Sprints

The container: Chapters

Work in the Applied Science framework happens in 6-week cycles I call Chapters.

A Chapter is a strategic container with a single governing direction, expressed as a master hypothesis. Sometimes that hypothesis is market-facing: a belief about buyers, urgency, and adoption that must hold for the company to work. Sometimes it’s technical: a belief about what you can actually build, and what it will cost in complexity, reliability, and time.

In principle, one Chapter should hold one master hypothesis. In practice, depending on resources and maturity, you can sometimes carry two, but rarely more. The cleanest version of “two” is when you’re straddling two distinct uncertainties: a go-to-market question and a build question. Will anyone buy this, with these constraints, at this price? And can we actually build the minimum surface area required to test that purchase intent without turning the company into a science project?

Earlier than that, the question often isn’t “will they buy” yet. It’s “what form of this idea is legible to the market today.” You’re searching for a wedge the market can immediately read: a concrete workflow they’ll delegate and a proof point that makes it feel safe.

Six weeks is long enough to build something real, and short enough to keep you honest. That’s the practical reason Chapters are six weeks.

The more important reason is decision cadence. A Chapter creates a date where you have to decide. It cuts off the endless “one more iteration” loop and gives you a temporal boundary your brain can’t negotiate with. The operating rule inside a Chapter is fixed time, variable scope. If the work is too heavy, you don’t negotiate the deadline, you cut scope.

The point of a Chapter isn’t to ship a lot. It’s to run the highest-quality sequence of experiments you can fit into six weeks, so you can make a real decision when the Chapter ends. You start with the master hypothesis, then design a chain: each experiment reduces a key uncertainty, and earlier results shape what you do next.

One Chapter might be market-heavy: build a demo that makes the value concrete, show it to fifteen target buyers, and test a few ICP slices to see where urgency and willingness to change behavior concentrates fastest. Another might be technical: prove you can execute the core workflow end-to-end under real constraints.

In market Chapters, the outputs aren’t “we built a demo.” They’re patterns: which ICP leaned in, which language triggered recognition, which objections repeated, and what the buyer asked for next.

In technical Chapters, the outputs aren’t “it works.” They’re failure modes, reliability costs, and whether the architecture is converging toward something you should commit to for another Chapter.

The heartbeat: Sprints

Inside a Chapter, there are three 2-week Sprints.

Sprints are tactical containers. Their job is to turn experiment design into execution. Chapters decide what we’re trying to learn by a deadline. Sprints decide what we’ll do in the next two weeks to force reality to answer. Each Sprint begins by turning an experiment into a protocol: who we’ll test with, what we’ll ship, what we’ll measure, and what would count as a pass or fail. Then we run it.

Every Sprint must ship something that moves you closer to proving or disproving the Chapter hypothesis.

You pick one or two experiments, then write a simple protocol: what you’re testing, how you’ll test it, who you’ll test it on, and what would count as a pass or fail. You also name the artifact you expect at the end. This could be a demo app, a workflow spec, an ICP map, a “why now” narrative doc, etc. Artifacts turn learning into memory. Without artifacts, teams “learn” the same lessons repeatedly because nothing gets carried forward.

Then you execute. The Sprint plan is the contract. New ideas are noted, but they wait until the next boundary. That’s the cadence doing its job: focus during the Sprint, creativity at the edges.

Every Sprint ends with synthesis. You answer four questions in plain language: what did we observe, what did it imply about the master hypothesis, what surprised us, and what decision does it force about the next Sprint’s experiment slate.

If you’re doing market work, synthesis looks like patterns in objections, language that reliably triggers recognition, and whether the buyer took the next step without being dragged. If you’re doing technical work, synthesis looks like failure modes, reliability costs, and whether the architecture is converging or expanding.

There’s also a social purpose here. Collaboration is highest leverage at the boundaries and tends to become noise in the middle. So Sprints deliberately alternate between intense alignment and quiet throughput. The team gets long, uninterrupted stretches to build and run experiments. You still move fast, but it’s a calmer speed: fewer meetings, fewer reopened debates, fewer half-decisions. People can hold a thought for more than five minutes, and the work starts to compound instead of thrash.

Chapters end in decisions. Sprints produce the evidence.

Outcome-based Kill Gates

Kill Gates exist at two levels: they gate Sprints, and they settle Chapters.

This is where the system stops being a cadence and becomes applied science. Kill Gates are defined up front, during Chapter shaping and Sprint planning. Start with the hypothesis (master or child), describe what success would look like by the end of the Sprint or Chapter, and then invert it. The inversion is the Kill Gate: if the world fails to look like this by a specific time, we stop treating the hypothesis as alive.

A Kill Gate is the moment you ask: did we earn the right to run the next experiment in the chain?

A good Chapter has three or four Kill Gates. Not twenty. They should be legible, falsifiable, and tied to the uncertainties that matter. They do two jobs. They prevent narrative, and make planning easier. Once the Kill Gates are clear, you work backwards: which experiments produce evidence for or against each gate, and what artifacts must exist by the end of each Sprint for the next experiment to be rational.

That’s how Kill Gates connect to Sprints. Each Sprint ends with a gate-check. Clear the gate and you advance. Trip it and you change something while there’s still time: the experiment design, the population, the product tilt, or the hypothesis itself.

At the Chapter level, Kill Gates become the decision mechanism. You evaluate against the gates you defined at the start. As a default heuristic, if two of four gates are not met, treat the direction as compromised and reconsider the approach. If three are tripped, pause and evaluate whether the governing direction should be killed rather than rehabilitated.

Sometimes the decision is, “commit another Chapter to this direction,” which is a very different statement than “we’re building this.” Sometimes it’s “narrow to this ICP,” or “the workflow is right but the control surface isn’t,” or “this hypothesis is dead.” Once you decide, you work backwards again: what evidence would make the next decision obvious, and what experiments belong in the next Chapter?

The point is to preserve interpretability and time. Kill Gates turn six weeks into a controlled experiment with stopping rules. They force a decision, and they make the next Chapter easier to design because your work is systematic, not vibes-driven.

Startups are a stacked tower of risks: market, product, distribution, technical, regulatory and so on. Progress is retiring risks in the right order.

Chapters choose which layer you’re trying to de-risk next. Kill Gates keep you from building higher while the base is still moving.

The Clean-up Week

Between two Chapters, there is a Clean-up Week.

This week exists because well-run Chapters are intense. They compress effort, they pull you into tight execution, and they generate a surprising amount of data (e.g. customer reactions, edge cases, failure modes, pricing signals, objections). In the middle of a Sprint you rarely have the cognitive bandwidth to let any of it sit. You’re collecting reality faster than you can process it.

Clean-up Weeks are the deliberate step back that turns raw data into understanding. Different people assimilate at different speeds, but everyone benefits from leaving the frame of focused execution and giving the mind some quiet time to connect dots. The useful synthesis often arrives when you stop pushing and allow the evidence to settle. Stare at the wall, take long walks, reread the notes with fresh eyes, and notice what repeats. That’s not indulgence. It’s part of the method.

The week still has practical outputs. You close small loops that would otherwise accumulate into drag: sharp edges, reliability footguns, obvious debt. You convert learnings into artifacts the team can carry: a short Chapter write-up, updated hypotheses, refreshed Kill Gates, and a clearer map of what changed your mind. And you shape the next Chapter just enough that Sprint 1 begins with clarity rather than thrash.

Without this week, Chapters blur. You carry residue forward, and the Applied Science OS degrades into one continuous smear of half-finished work and half-made decisions. With it, each Chapter stays discrete: experiment, verdict, reset, then the next attempt.

Boundary conditions: keeping your bearings straight

At this point, it’s essential to note that not everything is under test all at once.

Chapters and Sprints exist under a mission umbrella. The mission is the boundary condition. It defines the direction of travel, not the exact path.

“To accelerate the world’s transition to sustainable energy.” - Tesla

“To be Earth’s most customer-centric company.” - Amazon

“To increase the GDP of the internet.” - Stripe

Notice that none of the above talk about how they will achieve the mission. They don’t name a wedge, a product, a channel, or a planning cadence. They state an invariant, then allow the implementation to evolve over time. The shape of the mountaintop should be clear; which face of the mountain you start climbing, or the one you pick to get to the next basecamp, are the variables.

You touch mission and vision only if repeated Chapters fail. Chapters are not about re-deciding why you exist.

A Chapter is a falsification container for a specific hypothesis at the current level of resolution. Tactically, it might be: will anyone pay for this in its current form? If the answer is no, the goal is to generate enough evidence in six weeks that you stop reopening that question. That new prior becomes stable. It becomes part of your world model.The next Chapter is not a new identity. It is the next best hypothesis for how to move toward the same mission.

Indeed, without boundary conditions Chapters become thrashing. But without Chapters, mission becomes mythology.

Operating the lab: leader and team, as one system

In early-stage work, “leadership” can’t mean distance from the work. The job is closer to running a lab than running an org chart. Someone has to protect the cadence, force decisions on schedule, and keep the team oriented around the same hypothesis. Call that person the editor, the lab lead, the dungeon master—whatever fits.

Their core responsibility is epistemic hygiene: shaping the Chapter, hosting the hard debates at the boundaries, collating evidence as it comes in, and breaking ties when the system produces ambiguity.

That doesn’t mean they’re in an ivory tower. They still produce data wherever they’re highest leverage: customer conversations, demos, synthesis, writing, sales experiments, instrument design, unblocking. The difference is that their involvement serves the experiment, not their ego. They participate in the work while also guarding the frame the work lives inside.

The team’s role is to take a fuzzy question and make it testable. They own chunks of the work end-to-end: turn a hypothesis into something you can actually put in front of the world, run it, and capture what happened in a form the team can reuse. Concretely, that might mean: building the demo and writing the script; finding ten target buyers and running the calls; shipping a workflow slice behind a feature flag; adding the one metric that tells you whether the workflow is being used, and so on.

Just as importantly, the team owns synthesis. They don’t report activity. They compress what happened into the handful of patterns that matter: what repeated, what surprised us, what changed our mind, and what we should do next.

One emergent property of operating this way is that you need less “management.” Context becomes shared because shaping is a product of debate, not a decree. Success and failure are legible because Kill Gates are defined up front. The direction stays coherent because the Chapter is a single governing hypothesis with a deadline.

That clarity makes ownership easier: people can take a slice of the experiment and drive it end-to-end without constant check-ins, because they know what they’re solving for, how it will be judged, and why it matters.

Shots at the bat: time measured in Chapters

One of the biggest benefits of this system is that it changes how you perceive time.

“Eighteen months of runway” feels like space. It reads like optionality. It invites softness. You can always tell yourself you’ll tighten up next month.

“Eight Chapters of runway” feels like physics.

Chapters aren’t calendar time in the abstract; they’re decision cycles. They’re discrete attempts to retire risk, and the moment you start counting your remaining attempts, the work becomes less romantic and more honest.

The other reason the framing bites is that progress isn’t monotonic. In a perfect world, you’d climb risk layers incrementally: each Chapter clears a foundational uncertainty, then you build upward.

In reality, you sometimes discover something terminal higher up the stack and you have to revisit the foundation. The wedge isn’t legible. The distribution channel doesn’t work. The technical approach is too brittle. You don’t just “iterate.” You reset the stack hypotheses, which effectively burns a Chapter without moving the tower upward.

That’s why months can be misleading. Months pretend you move linearly. You do not. You move step-wise.

This also forces a more forthright relationship with fundraising timelines. It’s common to say, “we have runway until X.” A sharper question is: how many Chapters do we have before we must raise, and how many of those Chapters are realistically productive given the probability of resets? If you think you have four Chapters left before a raise, you stop treating decisions as reversible, and you start acting like every Chapter is one of your remaining shots.

Chapters and long-range planning

Over time, the Applied Science framework becomes a practical way to do long-range planning without reverting to bottom-up roadmaps, which are often more performance art and less planning artifacts.

You still set a destination (e.g. ten months from now we want ten customers, a credible revenue run rate, repeatable conversion, a proof point that makes the next round legible), and then work backwards in Chapters, not quarters. What risks must be retired, in what order, to make those milestones plausible? Which Chapters are for legibility (wedge + ICP), which are for repeatability (distribution + conversion), which are for robustness (reliability + controls), and which are for scale (expansion + pricing + onboarding)? And how are they appropriately sequenced so that we can reduce churn in our progress?

Once you accept that Chapters are finite attempts, redundancy becomes expensive in a way months don’t capture. Doing something in Chapter 1 that only becomes meaningful in Chapter 5 isn’t “being proactive.” It’s burning an attempt before the upstream prerequisites exist. That’s six weeks of runway converted into churn.

So the planning problem becomes sequencing. You want the outputs of one Chapter to become the prerequisites for the next. Respect dependencies and you avoid rework; the same logic as not building the first floor before you’ve poured the foundation.

Practically, this means you front-load the most foundational uncertainties and delay anything that depends on them. You don’t polish onboarding before you’ve found a wedge that people will adopt. You don’t scale outbound before you have language that reliably triggers recognition. You don’t harden infrastructure before you know which workflow you’re committing to. You don’t design enterprise controls before you’ve proven anyone will delegate the action at all.

Then, as you retire risks, the “next stack” becomes visible. Early on you’re mostly de-risking legibility and feasibility. Later you’re de-risking repeatability: distribution, conversion, retention, operational reliability. Later still: unit economics, compliance posture, scale constraints.

Each layer changes what experiments are even worth running.

Why this matters beyond productivity

This system isn’t about being organized. It’s about staying sane.

Early-stage is prolonged exposure to ambiguity. Your nervous system keeps trying to close loops that reality won’t close yet. In that vacuum, the mind manufactures substitutes: urgency without direction, motion without evidence, opinions that can harden into identity. You can work twelve-hour days and still feel behind, because “ahead” is undefined.

A decision cadence turns ambiguity into discrete questions with deadlines. It turns existential dread into a finite number of Chapters. It gives your brain permission to stop spinning, because it knows when the next verdict will happen and what evidence will count. It gives you a way to be both intense and calm.

That’s what people miss when they describe frameworks like this as “process.” The output isn’t just throughput. It’s psychological containment. You can go hard for two weeks because there’s a gate. You can tolerate uncertainty because there’s a Chapter decision date. You can sleep because you’re no longer trying to resolve everything, all the time.

There’s also a tempo effect. When collaboration is concentrated at boundaries and execution is protected in the middle, the team stops thrashing. Work becomes smoother. And smooth becomes fast. Not because anyone is moving frantically, but because you’re not paying the hidden tax of re-litigation, context loss, and perpetual half-decisions.

Most importantly, it makes failure cheap. A failed Chapter is not a personal collapse. It is an experiment that returned a negative result. You move to the next Chapter with less shame and more information.

That’s what Applied Science is buying you: the ability to swing hard without hallucinating.

Closing

If you’re early-stage and you feel like you’re working constantly yet not moving, there’s a decent chance the problem is not effort, but decision structure. You’re letting the calendar drift and paying for uncertainty with narrative.

Set a decision you must make on a date. Build only what produces the evidence for that decision. Pre-commit to the outcomes that kill the idea. Repeat.

That’s the whole method.

And once you install it, you start to notice something subtle: the company stops feeling like a fog, and starts feeling like a sequence of crisp questions you can answer.

You are not standing in front of the gun. You are holding the gun.

___

We’re running this OS right now in a project that will go unnamed for now. It’s improved speed, decision quality, and wellbeing, without sacrificing intensity. If you adopt any part of it, send me the sharp edges: where it failed, what was gameable, and what you had to modify.