Your Custom Text Here

Bitcoin bubbles; the optimal distribution mechanism

Why planned fair distributions don't work for broad use cases - adapted from an internal memo drafted in May 2019.

Bitcoin’s volatility profile is - by now - the stuff of legends. Monumental, euphoric rallies give way to abrupt, violent crashes and proclamations of Bitcoin’s demise (380 and counting). Thus far, the cycle has repeated without failure, earning Bitcoin the “Honey Badger” moniker in the process.

As the current cycle is unfolding, behind the BTC/USD pair’s most recent gyrations, new types of participants are entering the market; traditional macro money managers (e.g. PTJ) and nation states (e.g. Iran) are becoming increasingly open about dipping their toes in the cryptoasset ecosystem.

With every new type of player that jumps on board, the likelihood of Bitcoin becoming a widely accepted store of value and the Bitcoin blockchain becoming a globally accepted settlement layer, increases. The “why” Bitcoin makes for a good settlement layer and store of value has been covered extensively. However, the “how we get there” remains somewhat elusive. In this post, I will attempt to unpack that.

Fair != Equal

Let's for a moment imagine what an optimal state of the Bitcoin network at maturity looks like; Bitcoin is a widely accepted global store of value and/or settlement layer; global institutions (e.g. central banks) are on board, co-existing with crypto-native actors (e.g. miners); market manipulation is too expensive to attempt, as are direct attacks on the network; BTC is distributed widely among holders, such that network participants extract maximum value by being able to settle with all other parties they may wish to, and that no party has disproportionate “bargaining power” over network outcomes, allowing participants in the network to be continuously incentivized to remain participants.

From the above, a “fair” allocation of BTC among holders seems to be a key underlying requirement for this future to come to bear. Note that “fair” is not the same as “equal”.

Fairness, in this case, implies that every participant’s utility function is maximized, subject to their unique constraints. Under that condition, “equal” is “unfair” and therefore, unsustainable.

If we assume the “fairness” condition as requisite, then while not necessarily an easy pill to swallow, the rollercoaster ride might be the *only* path available to get us there. To illustrate the point, an approach by deduction reveals why the competing approaches cannot work;

A centrally planned diffusion mechanism: this construct fails as the planner holds all the bargaining power - such that no other party would willingly opt-in. In order to be executed effectively, it would have to be orchestrated and delivered by a benevolent dictator (a party with perfect information and perfectly benign incentives), and for all participants in the network to trust that the allocator is indeed benevolent. In practice, impossible.

A diffusion mechanism planned by a “political” coalition: this can’t be orchestrated in a multi-party explicit negotiation format, because there are too many conflicting interests at play in order to implement top down consensus. If it is sufficiently hard to achieve with structures where there is some cultural cohesion (e.g. EU and the Eurozone), it should be near impossible to achieve at a global scale.

Economic bubbles as a by-product of fairness

So if we agree that neither of the two are viable options, the only option left is a free market mechanism; a continuous game, that is played by individualistic agents with hidden preferences, in near infinite (and infinitesimal) rounds, that allows for each participant to opt-in at the valuation that perfectly satisfies their objective function (what they strive to maximize under given constraints), therefore covering the full utility spectrum of the population of agents.

Hidden preferences become revealed ex-post and as such competing agents cannot devise a strategy that creates a surplus for themselves that leaves others at a deficit ex-ante, resulting to an ultimately fair distribution. And in the process of revealing preferences in a continuous game with infinite rounds, bubbles are created. Competing agents with similar objective functions are forced to respond to the first mover among their counterparts and jump on the bandwagon. Under scarcity, the price rallies, until the reservation price of agents that opted-in earlier is met. At that point the distribution phase begins, as earlier participants divest and get rewarded for stewarding the network thus far, by locking in a margin. As painful as the process might be, it ultimately yields to a fairer allocation.

As the "rounds" of the tacit negotiation - come free-market-bonanza - game unravel, the very nature of the platform evolves, opening up to a wider possible utility spectrum. With time, the network becomes more secure as wider margins become available for miners (either through higher prices or through advances in operational efficiency) and more resources are committed towards Bitcoin’s Proof of Work. It follows that as the network’s security improves, it opens up to new types of agents that are striving to maximize value preservation potential, subject to the liability they have to their constituents (measured as risk). The more types of agents there are on the network, the better a settlement layer it becomes, and so on.

Therefore, there is sense to the idea that progressively larger agents would opt-in at a higher prices, as they are effectively buying into a fundamentally different - and arguably better - network for value store and transfer. And with every new type of agent unlocked, the bandwagon effect re-emerges.

Conclusion

Bitcoin might not have been a secure or wide enough network for Square (an agent to its shareholders) to consider as its future payment rails and settlement layer in 2015. It is in 2020. Similarly, while Bitcoin might not be a secure or wide enough network for a sovereign to opt-in in 2020, it might be in 2025.

So, not only should we not be surprised by the new type of participant that is emerging in the early innings of this cycle, but we should expect more of this as the network’s value increases and its security profile improves.

And in the process, we should learn to accept the nature of the game.

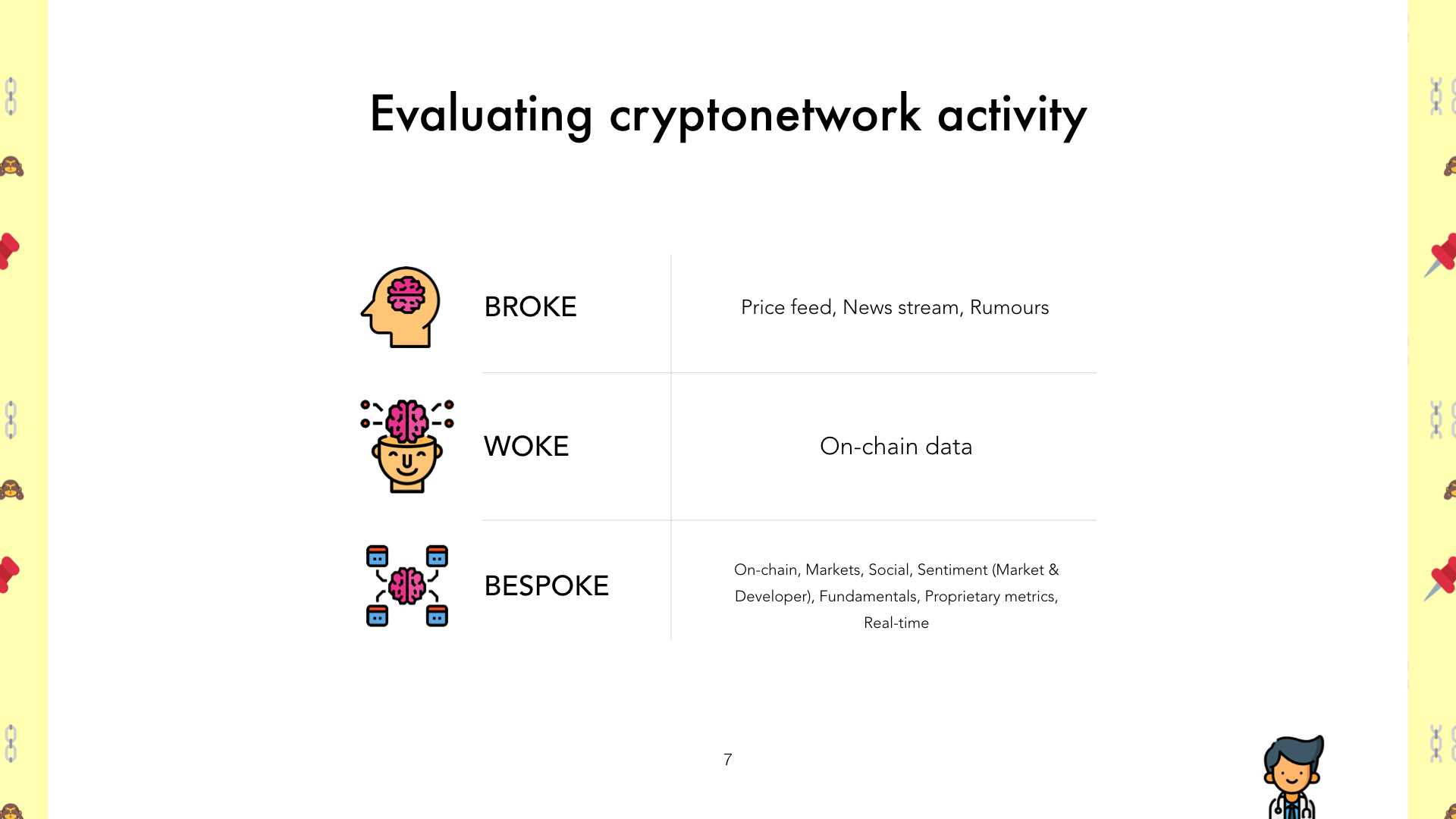

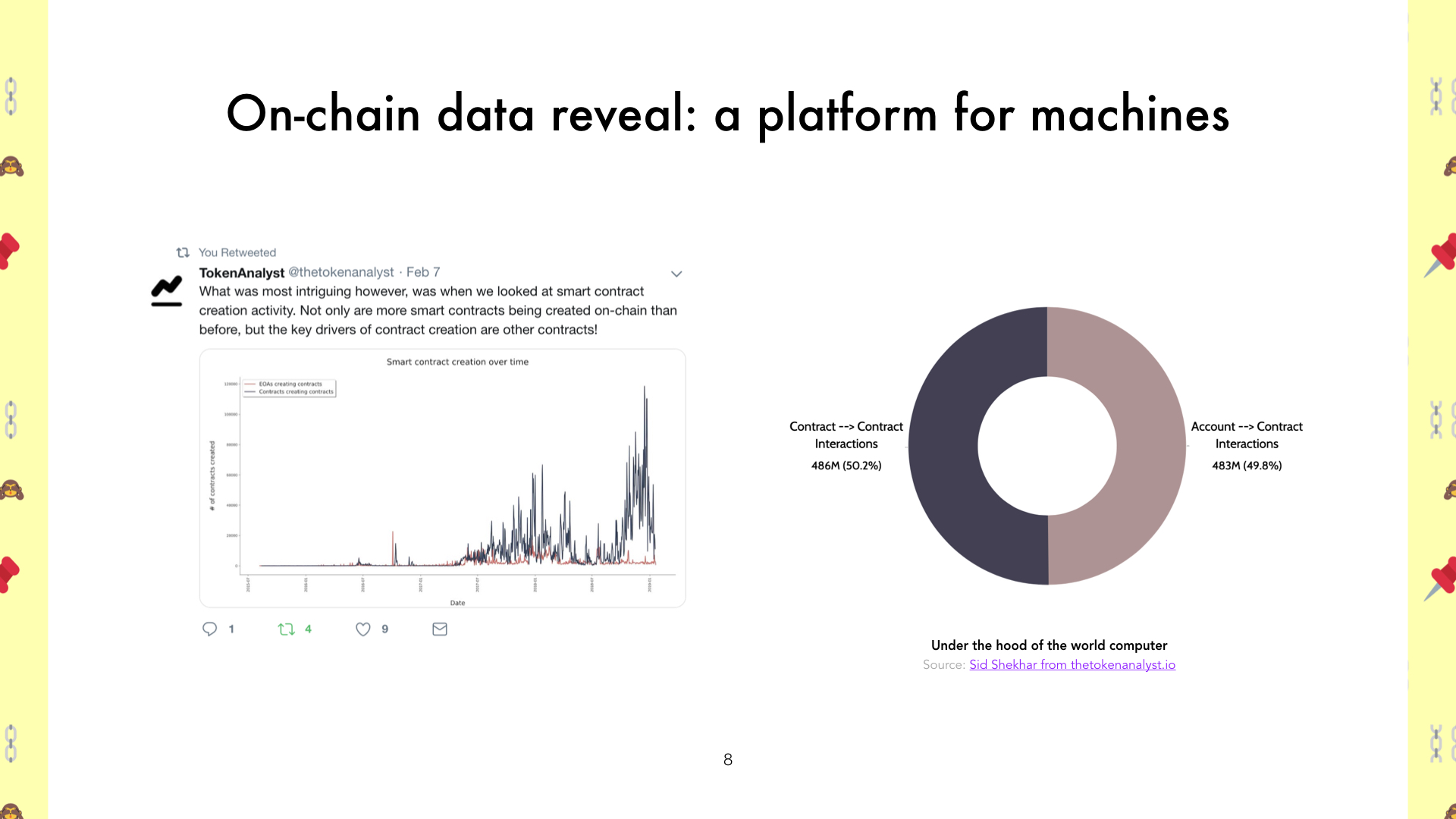

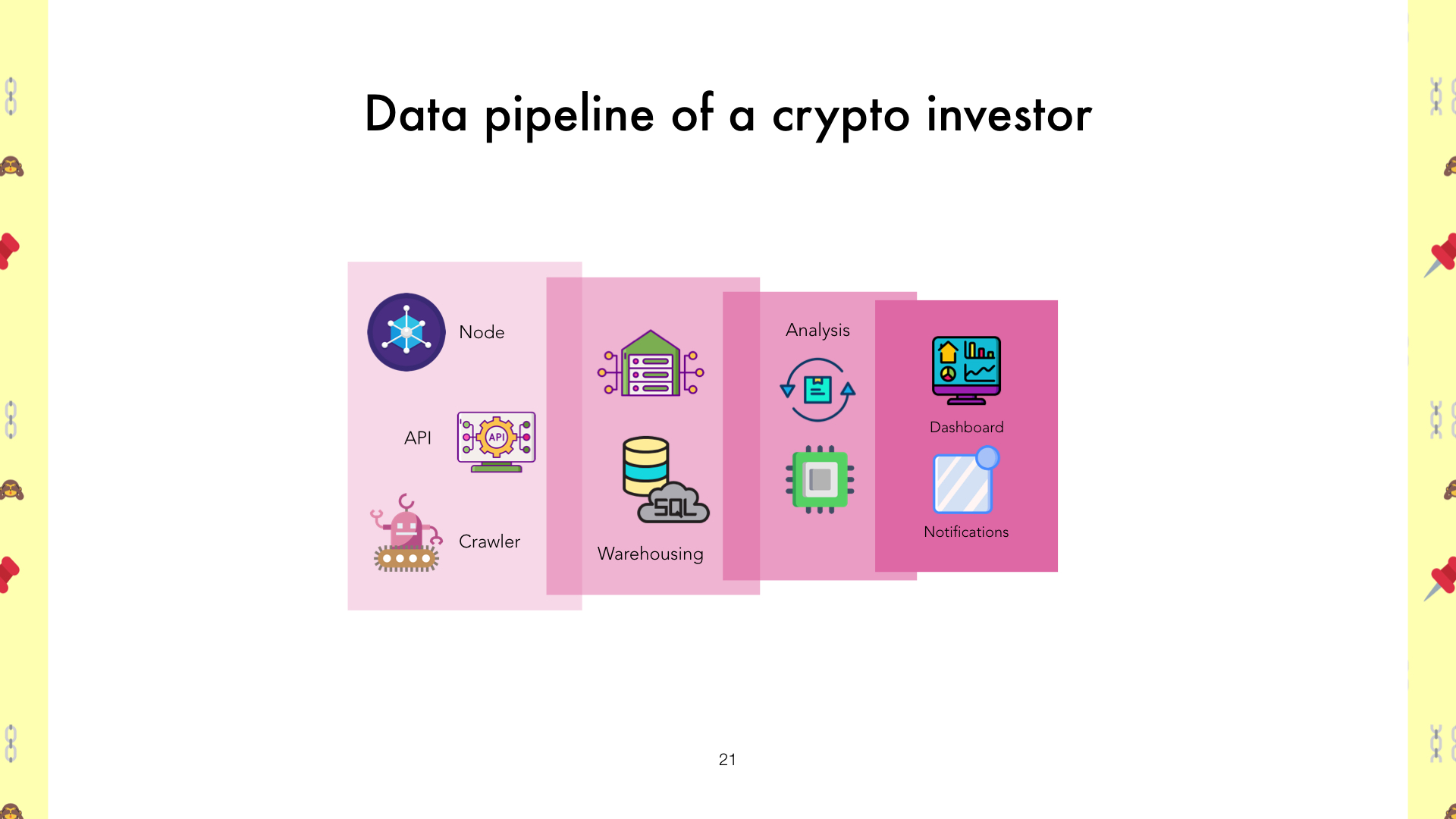

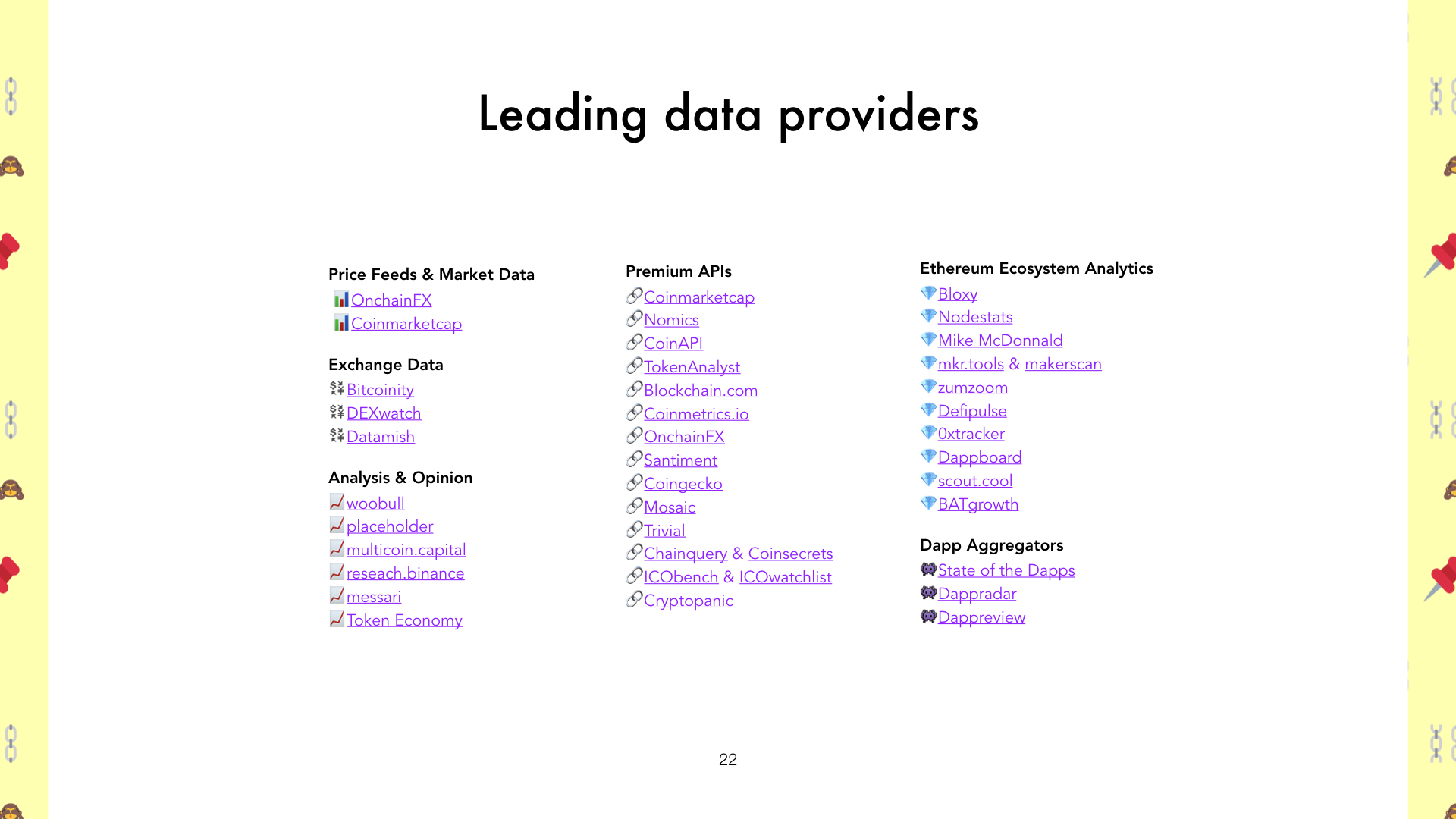

Using data to evaluate the health of cryptonetworks

Presentation for a talk I gave at the Data Natives meetup in London.

Can’t recommend them enough. If you’re into data and in and around Europe, it’s worth taking a look at their meet-ups and conferences.