Your Custom Text Here

Beyond the hype on terra.money

Key Takeaways

There is a hidden negative multiplier effect in the Terra system, that will dampen the price of Luna - until a network effect is reached.

There is a hidden viral loop in the Token economics, that incentivizes merchants to also be stakers and enlist as many other merchants as possible to drive their unit costs down.

The interplay of the two loops optimizes for long-term oriented actors to populate the consensus layer, a net positive.

Both the decision to start with Korea, and the go-to-market strategy Terra is deploying, are moats in the making, if executed well.

Luna lost ~75% of its value since listing in Q3 2019. At current prices, pre-sale investors are likely at break-even, having already booked (some) profit.

Conservative estimates from a DCF model, show that Luna, at current price levels, is undervalued by between 38% and 67%.

Terra.money; seigniorage shares done right

Terra is a stablecoin project out of Korea that deploys a seigniorage shares model in order to algorithmically ensure stability in the system. This is not the first time we see an asset of this type hit the market - Basis and The Reserve are the two most prominent ones that jump to mind. However, where its predecessors have thus far failed, Terra is getting promising traction.

Terra's base layer token economics

Terra is essentially composed of 2 tokens that live in parallel; Terra and Luna. Terra(X) is the stablecoin component - where (X) is any fiat equivalence supported on Terra (e.g X = KRW, USD etc), and Luna is the protocol token. Terra powers the user facing part of the terra.money platform, while Luna - a fixed supply variable price token - powers the infrastructure.

The blockchain layer in Terra collapses the multiple layers of payments processors present in modern day e-commerce and P2P payments value chains, and manages to reduce the cost of executing transactions by as much as 80% - ledger fees start a default of 0.1% and are capped at 1%. Validators have to stake Luna in order to be granted the right to validate blocks and access a perpetual stream of ledger fees as a reward for their work - and equivalently are exposed to slashing if they are found to misreport ledger state. A validator's Luna stake represents pro-rata odds of generating Terra blocks; i.e. the more Luna you stake, the higher the expected value of the rewards you claim. Luna holders are also granted governance rights over the fiscal stimulus treasury - endowments to dApps that apply to the Terra ecosystem.

How Terra maintains stability

Terra maintains stability by algorithmically adjusting the money supply. In an excess demand condition, where Terra would go off its peg on the upside, the system mints more Terra and burns an equivalent (according to the spot exchange rate) amount of Luna. Conversely, when Terra is experiencing a lot of selling pressure, the system mints and auctions more Luna in order to buy back and burn Terra - contracting the money supply and diluting Luna holders.

A hidden negative multiplier effect in the stability mechanism

Herein lies the first issue with Terra's model; validator dilution. Until the stablecoin instrument has enough brand recognition, trust and ultimately network effect, so that the perceived risk of holding Terra on balance sheet is low, merchant incentives remain somewhat warped. Here's what I mean:

1 unit of TerraUSD on balance sheet is worth less than 1 unit of fiat USD, due to their differing counterparty risk profiles.

The former is backed by a consortium of private actors, while the latter is backed by the US government. Until a network effect enough strong enough to persuade merchants otherwise is in place, they are incentivised to offload that balance sheet risk and head for the nearest exit to government backed fiat.

The effect is continued dilution for Luna holders.

Similarly, in the pegging process described earlier - where equivalent values of Terra and Luna are arbitraged away to bring the peg to balance, in order for the arbitrageur to book profit, they need to immediately liquidate the Luna they receive in equivalence. If that incentive structure holds, then not only are validators diluted by inflation in the short term, but the value of their Luna holdings reduces further as market makers immediately offload the minted Luna to market, increasing the available supply of the asset. Absent a network effect, this dynamic acts as a negative (unintended) multiplier in the Terra system.

Compensating validators for dilution

To incentivise validators to weather the storm, Terra introduces long-term validator incentives in the form of inflationary rewards (currently ~10%). Effectively Terra is inviting potential validators to ride out the J-curve with them and collect beans in the process. At a high-level, the idea makes sense; the negative multiplier effect should hold only until the network effect is reached. Once that is achieved, then the loop should turn from adverse to virtuous, and value would start to trickle back into Luna tokens.

A hidden viral loop in the token economics

Things get interesting when the boundaries between merchant/user of the Terra blockchain and validator start to blur. There is no provision in the model to explicitly prohibit merchants from also become holders of Luna and validators in Terra's consensus. In fact, it seems that Terra implicitly optimizes for that. Of course, not all merchants will wear investor hats, but potentially the more savvy (and dare I say the more influential) will recognise that since they are already long the platform as early adopters, they can leverage up on the upside by staking Luna, while reducing their unit costs and hedging the downside, by collecting ledger fees.

Now were that the case, merchant validators are even more incentivized to evangelize Terra; the more merchants on the platform, the more ledger fees they would collect, the more their unit economics would improve and the quicker the platform would get to the critical inflexion point, after which the Luna economics turn positive.

As positive as this might be though, so long as local governments remain skeptical of cryptoassets, it is unlikely that this viral loop will be activated.

Demand for txs = value appreciation for Luna

By now, it should be clear that Terra has been architected in such a way, that makes demand for transactions the critical variable in its value model. So far, the team has implemented 1 stable pair - the Korean Won (KRW), with plans to expand in a multitude of currencies that include the USD and the IMF's SDR.

From a strategic standpoint, the decision to start with the KRW seems smart for a couple of reasons; (i) Korea is one of the most technologically advanced countries globally, with the 2nd highest % of Information and Communication Technology as a proportion of GDP, and 2nd highest % of R&D spend among OECD countries.

Not only does that improve the adoption potential for Terra, but also (ii) given the relatively insular nature of Korean currency markets (see: Kimchi premium), it provides for a "natural" incubator by protecting Terra from external competition. That allows Terra to iterate fast and capture market share in the Korean and ASEAN markets, leveraging local networks, while ironing out the model and improving its potential for further expansion.

Further, the team has explicitly targeted e-commerce as the first market they will be focusing on, a burgeoning industry that has been experiencing anywhere between 5% and 65% CAGR in the region, over recent years. One of Terra’s core strategies is to build an alliance of e-commerce sites and operate as a payment platform for them. The Terra stablecoin may also be offered as an incentive for those making purchases on these sites - a strategy that is serviceable due to the cost efficiency that Terra's blockchain back-end achieves.

In order to bolster their go-to-market capabilities, Terra launched CHAI, a consumer facing e-commerce application for everyday purchases (to illustrate, a large proportion of purchases are reportedly for rice) that works with Terra's blockchain as the back-end payment rails. According to reports from Terra, CHAI has seen 250k sign-ups since launching a few months ago, with $1.3M volume processed.

A quick look at the Terra block explorer points to an approximate equivalent $1.5k as the current daily transaction volume - a figure that pales in comparison to legacy internet native competitors. To illustrate, appox. $200M daily volume processed by Adyen, a Dutch competitor of Stripe that recently underwent an IPO at an $18B valuation. Be that as it may, in the short few months the platform has been live, volume has been growing linearly, showing a healthy - albeit pre-exponential - growth pattern.

While somewhat protected from global markets competitors, Terra faces strong domestic competition from Kakao/Klaytn (who has also a stake in Terra), Toss and other legacy payment solution providers.

Should one be a buyer of Luna at this point?

Terra has secured $32M from Polychain, Arrington XRP and Binance Labs - among others, in a sale that concluded in September 2018. Various ICO listing sites point to the ICO price per Luna token, standing at $0.80. Given the pre-sale patterns we have seen over the years, we could speculate that the price that early investors came in is closer to to $0.2. Anecdotal information we have collected, point to Luna tokens changing hands OTC pre-Mainnet for as much as $2.4 per Luna, which would have put early investors at over a 10x return at that point.

Currrently, the token is trading at $0.43, having listed at approx. $1.7 per token; that's a 75% drawdown, that puts the early investors in the 2x gain region - likely with more realised already, and less of an incentive to sell down on the remainder of their positions.

Arguably, one could pick a worse moment to start building a position, although the lack of liquidity might prove to be an issue, depending on the intended position size.

My take on Terra's valuation

To further put some context on current price levels, I went ahead and built a DCF model to value Terra. The premise is that a DCF model applies really well to valuing Luna tokens, as staking Luna is a claim to a stream of future cash flows (tx fees).

Model assumptions

I benchmarked the 3 industries that are most relevant to Terra (shown below), projected their growth in tx volumes according to 3rd party estimates over 10 years, estimated how much share blockchain based solutions are poised to capture over those 10 years (different S-curves) and made an assumption on the proportion of the blockchain quadrant Terra is likely to represent in each industry.

The main assumptions that govern the model beyond the ones mentioned above, are:

a 0.35% tx fee - adjusted downwards from the average {0.1% to 1%} to reflect the cost of running a validator

a 40% discount rate - industry standard for VC

an 80% main use case contribution level - assuming that most of the value transacted on Terra will come from the 3 industries benchmarked

a 25% staking rate - reflecting the current state of Luna staking / total supply

a 2% annual growth rate after the 10 years modelled to capture the terminal value

You can access the model and try your own assumptions here.

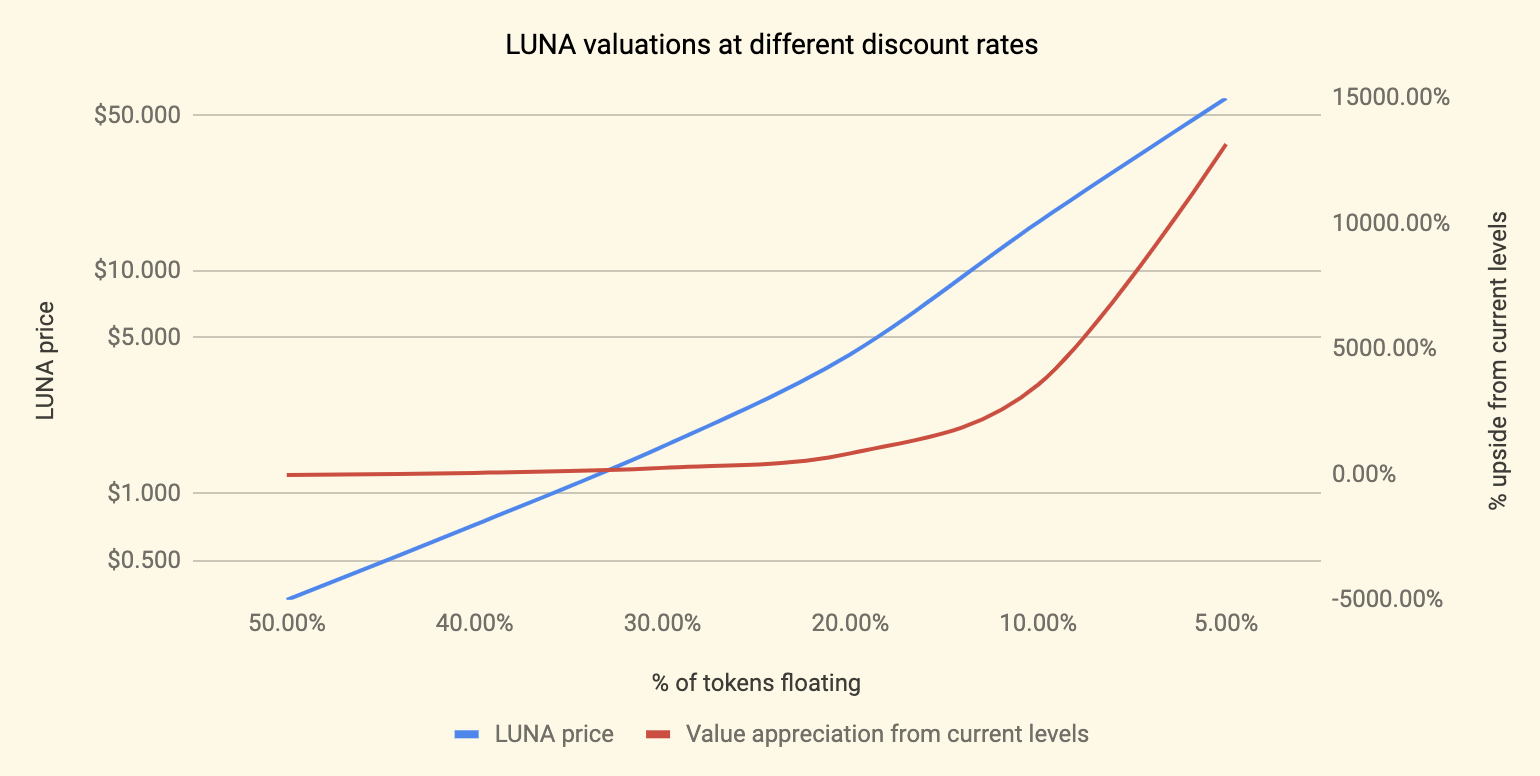

The result on the base case scenario, is an estimated $0.72 per Luna, at a $180M network valuation.

What is interesting about the result is that in a scenario building exercise (changing one of the key variables and keeping all else constant), the base case outcome sits a few standard deviations to the left of the mean, implying that at this point there is more upside to owning Luna than downside.

To illustrate, if we assume that 50% of the tx volume on Terra will come from other than the 3 main use cases, then the fair price per Luna token stands at ~$1.3 (3x from current value). If we further relax that assumption to 10%, then the projected upside stands at 10x. Equivalently, while exploring different discount rate levels (reflecting different levels of perceived risk), we find that a 50% discount rate yields a fair price of $0.33 per Luna (a 25% downside), while a 30% rate yields $1.62 per Luna (a 4x outcome) and so on.

What is rotten in the state of Denmark...?

There is a lot that's right about Terra; a great team, a straight-forward token model, a very technology-friendly home market, the potential for explosive growth in the coming years, an attractive current valuation and not many project specific risks. Regarding the latter, there are three main risk drivers that I see here - namely (i) the hidden negative multiplier - covered in an earlier section, (ii) the risk that price oracles introduce in the model, and (iii) the time-lags that exist in the stabilisation model.

As far as (ii) is concerned, this is a problem that underlies the whole blockchain industry and as such I am more inclined to bucket as a systemic type risk. There are currently many solutions being iterated upon, including some higher profile ones from Chainlink and Maker DAO, but also some newer ones like DIA.

Regarding (iii), this is something that I need to spend some more time thinking on. The risk here lies in that the supply side mechanisms that ensure the peg remains stable, will be slow to react to demand side fluctuations - or that the market won't pick them up soon enough. At the scale Terra is at now, the effect should be miniscule.

However, in a condition of large transaction volumes, this could lead to poor price discovery for Terra users and a lot of unintended costs creeping up on merchants' and users' balance sheets.

Parting thoughts

Doing some quick mental accounting on the case presented above, it is fairly clear that the upside here outweighs the downside. The combination of a great market, a great team, an appropriate price point and a novel configuration of blockchain technology in collapsing unit costs, make Terra/Luna an attractive opportunity. If there is ever someone to disrupt Paypal and Stripe, they are likely to look like this in the back-end.

Were one to hold Luna, the incentive is for them to have a long-ish hold horizon, while they would have to be prepared for the potential of further short term value depreciation. However, if there is fundamental belief in the team's ability to execute and the existence of a large enough market for Terra, then the risk is likely a risk worth taking.

And as always - this is a business case exploration and not financial advice. Be safe out there.

A model at odds; reviewing Brave’s token economics

Takeaways

Brave is a standout among crypto projects from the ICO era, when considering the adoption it has managed to drive.

The MAU numbers are still low, when compared to other browser products.

BAT, the native protocol asset, only finds utility as a payment token, which dampens Braves adoptability.

While the adoption numbers are encouraging, more users doesn't necessarily translate into more ad spend, as Brave's core value proposition is ad-blocking.

The ads shown on Brave Rewards are mostly of poor quality and still very crypto specific. Better quality ads and better payouts to users (currently $0.5 pcm) will improve adoption.

Brave is one of the breakout crypto-friendly products to come out of the 2017 ICO boom. The browser is a privacy-first product, offshoot of Mozilla Firefox and fork of Chromium, powered by a cryptoeconomic layer in the back end. Instead of a traditional advertising model, Brave shares 70% of the ad revenue generated, with users, in the form of Basic Attention Tokens (BAT). Whether a user is exposed to ads or not, is up to the their discretion.

Adoption

Recently, the browser surpassed 8M MAU, a YoY growth rate of 166%. While the absolute figures pale compared to Chrome's 3B users, they are certainly outstanding in a crypto context. If the assumption that internet users across the world will increasingly keep becoming privacy sensitive holds true, then a window of opportunity opens up for Brave. On the browser end, Brave is faster than Chrome, while its integration with Duckduckgo on the search engine layer, boosts its privacy preserving value proposition.

Whether or not Brave is an attractive investable opportunity through BAT, largely depends on BAT's token economics. BAT is the native network token that is primarily used as a payment token, in the exchange for attention between advertisers and users. While an ad-blocking browser by default, in Brave users are presented with the option to share their data with advertisers, and see ads in exchange for BAT.

1.5B tokens were issued and distributed over 85% to investors and the wider market - a big long term positive in my book. Until further notice, there will never be any inflation - also a big net positive. BAT tokens have no further intended utility than the payment function described above - a feature I perceive as a net negative.

The numbers of publishers signing up to the Brave ecosystem are steadily increasing. The more publishers there are on the platform, the more attention there is on the platform and thus the more attractive it will be for advertisers to use Brave instead of competing ad networks. In order to do that, advertisers will be required to build up BAT reserves to pay users with.

Over the long term, advertisers would have to engage in some form of reserve management on their BAT holdings, in order to lock down a best price in terms of USD, and optimize their cost basis.

The model is already getting some traction, most of which comes from the crypto-native community. The quality of ads that Brave shows is relatively low, with the majority of the advertised brands being VPN and exchange products. Unsurprising - given the type of user that has become an early Brave adopter, but for the product to become stickier, I feel we would have to see better quality advertising.

Brave token economics from the ground-up

Earlier on, I mentioned that I see BAT's utility as * only * a payment token, as a net negative. The reason why, is that it introduces a lot of overhead for advertisers. There is virtually no reason for merchants to adopt a highly unstable currency equivalent as means of payment in order to reach audiences, except perhaps for if they are long the platform itself - in which case the presumption becomes that every merchant will wear an investor hat. Even then, the case for pure payment tokens is grim as the aforementioned adoption mechanism is a zero-sum game.

If the majority of token economy participants decide to just build up reserves of the native payment token, you would have to assume that their involvement in the Brave ecosystem will not drive the majority of their business, so long as running costs cannot be covered using said token without exchanging it for fiat. In itself, that limits the addressable market.

Now, if the majority of participants decide to not be exposed to volatility and sell down on their token denominated income immediately upon receiving it, then everybody else is incentivised to do so - or be left holding the bag. If we agree that this dynamic is true, then it creates the perfect conditions for a race to the bottom.

The final argument that could work in Brave's favour, would be that the product will be so irresistible and as such attract so many users, that it will be impossible for advertisers to ignore it.

This could be the case for Brave, only it can't, as long as its core value proposition is - quite literally - blocking ads.

I have been using Brave with the Rewards feature on for 3 months now as an experiment and earned 5.9 BAT thus far, which amount to $0.5 pcm at current prices. In western world standards this is inconsequential. Personally, I would rather pay 3x as much to not have to bear with ads.

It’s neither stable, nor volatile - what is it?

For almost 2 years now, BAT's price has ranged between $0.15 and $0.50, and while that makes a good case for relative stability enforced by market forces, it certainly is not as good as a stablecoin's, while it doesn't seem to have the potential for a moonshot either.

Given this PA history, one would expect those advertisers that decide to build BAT reserves to drive up the price to ~$0.5, at which point cyclical sellers would be triggered and they would drive the price down again. Conversely, at prices near the $0.15 level, utility seekers would start buying up reserves again. Without a systematic mechanism to break the cycle, I could see it just endlessly repeating. Good for the speculator that is interested in taking advantage of that cyclicality, but bad for almost everyone else.

A better model would be one predicated on some sort of stablecoin, where BAT would be the protocol asset that would give validators that would stake it access to ledger fess. We are increasingly seeing traction in the work token space, with Terra's dual token model providing for a good example. More on that, in a future post.

TON; a sleeping giant awakens

The Telegram Open Network (TON), is the most eagerly anticipated Mainnet launch in 2019 - and not without reason. TON has conjured up the 2nd largest fundraising effort in crypto, second only to that of EOS, and promises to launch a 5th generation blockchain that introduces its native asset, the Gram, as a payments tool to approximately 250 million active users of the Telegram Messenger.

But not all appears to be rosy over at Telegram HQ. The project is late in its roadmap by more than one year, and has only recently released a public Testnet, with all too many variables being currently classified under “unknown”. TON is faced with a dire dilemma; either deliver a working Mainnet by the 31st of October, or return capital to investors.

The small ecosystem around TON is currently seeing a flurry of activity as the deadline approaches fast, with mystery abound as the core developer team continues to keep a very low profile. Will the network launch in time? Will it be sufficiently decentralized? Will it attract the necessary developer interest to populate the network with applications?

In this report, I provide answers to above questions - and many more, in what is possibly the most comprehensive piece of research on all-things TON.

Beyond the hype on xDai

Aka, the DAI of DAI, the native Ethereum stablecoin for fast and cheap P2P transactions, and one of the more hyped projects to come out of the Ethereum developer ecosystem in 2019. By way of xDai recently raising a $500k round led by B-Tech - the investment arm of BitMax.io and Focus Labs - the project came to my attention recently and thought it would make for a good Daily exploration. So without further ado, I'll take some time to present you with the TL;DR on xDai, along with a few quick-fire thoughts on what's good and what's not about the project.

What is xDai?

xDAI is both an Ethereum sidechain, and a token that is pegged to the US Dollar via the DAI, has extremely low transaction fees, and very fast transaction times.

The project was brought to life in a collaboration between POA Network (one of the more active developer teams within Ethereum) and Maker DAO. Users can convert Dai to xDai via POA Network’s TokenBridge, which connects Ethereum and xDai chain.

How does xDai work?

The xDai blockchain is a wholly separate network from the Mainnet that achieves much higher throughput by scaling up the block size and scaling down the block producer (validator) count. The sidechain mechanism is powered by POA's Tokenbridge, and as such requires an own set of validators, separate to those active in Mainnet.

xDai works with 10 validators that are responsible for running nodes and setting the network parameters.

The way xDai is minted works as follows: you lock DAI in a contract on Mainnet, and the validators on the xDai chain mint DAI on the xDai chain to you. Effectively, xDai trades decentralization for performance.

Why xDai and not just DAI?

As a Mainnet token, the DAI is subject to the wild fluctuations that transaction costs on the Ethereum network undergo - tied to a large extent to the availability of resources on the network.

The chart below shows how the history of the median transaction fee on Ethereum, since Q3 2017. Indicatively the median tx fee for 2019 is close to $0.1.

Via the sidechain mechanism (and some sort of transaction batching/key-synching bridge with Mainnet) xDai manages to perform transactions at a steep discount to DAI on the Ethereum Mainnet. More specifically, the cost to perform a transaction on xDai, is about $0.000021.

As we explored above, more recently the same function in Ethereum costs 4000x more (or 0.25% of the transaction value on average), while in the normal financial world, with what it costs to send money in the normal the cost of money transfers is upwards 3% (for international transfers).

Similarly xDai records impressive performance in the transaction speed dimension too. Transactions on the xDAI blockchain occur within five (5) seconds, while a typical Ethereum transaction takes about 1–3 minutes and a normal financial world international transfer, way over 24 hours.

And what about early traction?

Established in October 2018, xDai Chain has attracted the attention of the ecosystem, thanks in no small part to Austin Griffith’s Burner Wallet, which provides a quick and easy way to carry and exchange small amounts of spending-crypto using a mobile browser and serves as a low-friction way to onboard new users.

xDai was used at ETHDenver (Feb 2019) as a platform for the Burner wallet, which allowed thousands of attendees to seamlessly buy food and transfer funds. 11 food trucks accepted xDai via Burner Wallets and sold 4,405 meals for a total of $38,432.56. And the total fees were only $0.20.

xDai was also used during ETH New York, though no similar figures have been made public. Beyond that, there is only one Dapp outside the wallet contingent that uses xDai - and that is the somewhat fringe prediction's market Helena.

Having reviewed what xDai is and how it works - brief as it might have been, let's now consider what xDai has going for it and where it falls short.

In favour of xDai...

- Ultra fast and cheap transactions with stable value. Could really be a game changer for Dapp adoption by providing a significant UX improvement.

- Can see it having significant impact in P2P payments (although one can argue that this is not really a problem in the developed world).

- Supported by two of the strongest developer groups in crypto (MakerDAO and POA).

Against xDai...

- Pegged to DAI, therefore pegged to USD, right? Wrong! The DAI is notorious for breaking its peg with the USD.

- If Ethereum eventually scales via Ethereum 2.0, then xDai is obsolete, as the DAI itself will enjoy similar transaction speed and cost.

- Clunky UX; like with many things in crypto, getting xDai as a user, is far from easy. A user journey would look like this: buy ETH on Coinbase (Pro) with USD, exchange ETH for DAI, transfer the DAI to the Dex Wallet mobile app (dl the app), and exchange DAI for xDAI. Far from ideal.

- Adoption story is over-sold; a quick glance at the types of transactions taking place on the xDAI chain, show virtually 0 P2P usage. Contract call type transactions are disproportionately high, while the most common USD amount transacted comes with 4 to 5 decimals.

- Centralized; 10 validators control the parameters of the ecosystem. This might not matter much as long as xDai is inconsequential, but will certainly matter if/as things progress (e.g. see EOS).

For all its promise, xDai seems to lose out in a tit for tat and leaves the observer with much more to be desired...

A commentary on Burniske's "cryptocommodities vs cryptoassets"

Chris Burniske recently published a blog post titled "Value Capture & Quantification: Cryptocapital vs Cryptocommodities" as an attempt to extending and amending his popularized framework of valuing cryptoassets (MV=PQ) - which you can access directly here. In today's edition I'll provide a summary of the key propositions.

The extension of the thesis, introduces an important distinction of all cryptoassets in two main buckets; cryptocommodities - non-productive digital assets (e.g. Bitcoin) and cryptocapital - productive (stake based) digital assets (e.g. Cosmos ATOMs). The following table provides a conceptual backdrop for the two clusters, borrowed and adapted from Robert Greer's (1997) framework of defining different types of assets.

Burniske asserts that one's best bet in valuing cryptocapital, by merit of its potential for productively generating returns, is a customized DCF, while for non-productive cryptocommodities, the best approach is probably still some rendition of the MV=PQ equation (e.g. NVT, MVRV).

Getting more specific into what constitutes cryptocapital, Burniske offers a loose definition as "any asset that is staked, bonded, or otherwise committed in orderto get a claim on value flows. "Given that within the proposed framework no cryptoasset is of a purely singular nature (CA+CT/A), it is implied that some part of its value might be calculated via a DCF and some other via NVT - though it is further implied that the consumable part might often be negligible, given the supply side insulation that many of these assets are subjected to. What this means is that these assets are used by the supply side to secure the network, and might never be used as demand side instruments.

When considering cryptocommodities, things are presented in a more straightforward fashion - as this strand of thinking has been around for a little longer, and iterations exist since Burniske first proposed the model in 2016. Here's an example of an attempt at valuing cryptocapital from HASH CIB btw, where CUV - current utility value = PQ/V

SoV type assets are presented as an add-on property to cryptocommodities, that according to Burniske make the asset display the unique property of perfect hardness. According to the author, few commodities make the leap into being considered reliable SoVs and for the cryptocommodities that don’t achieve the financial premium associated with SoV assets, their value capture prospects are grim. Here's how this "superclass" is characterised in the whitepaper;

A couple more interesting assertions being made in the paper are that:

commodities are typically thought of as having a floor at their marginal cost of production - and Bitcoin seems to so far exhibit similar behaviour (miner's PnL).

in a digital world, there is no natural consumption/destruction of the commodity - which is where the artificial constriction of supply through forced burning and extreme scarcity becomes vital (bye bye GRIN).

most physical commodities have marginal costs of production that fall as the systems cales in its ability to extract it - in crypto it's the opposite.

assets that have to be somehow put to work to earn residual income, are distinctly different than assets on which passive income is earned, and therefore are more difficult to define as securities.

But perhaps the most valuable takeaway of all is the following:

It is becoming increasingly clear that for a token economy to attract value, there has to be some form of stake and/or work involved - the clearer the implication, in fact, the better - as the closer we get to repeatable business/network models, the closer we get to the promised land.

Beyond the hype on Maker DAO

Part 1

For the next few editions I'm going to dig into DeFi's most prized asset - Maker DAO. Being cognizant of time limitations here, I'll break this up into multiple pieces - which will hopefully make it a little bit more digestible for all. Maker has conjured up a lot of excitement among the community and for good reason, as at the moment around 2% of all the ETH in circulation is locked up in the Maker smart contract.

What exactly is Maker though? In short, Maker is a set of smart contracts responsible for the issuance of the DAI stablecoin (pegged to the dollar). DAI is backed by Ether that is locked into the Maker smart contract as collateral - see below for a glimpse of the UI.

As an ETH holder, you can lock up your ETH as collateral and issue an equivalent amount of DAI. This function is known as a “collateralized debt position” or CDP. Due to the volatility of ETH, the amount that needs to be provided as collateral is a multiple of a 1:1 relationship, to prevent positions being liquidated on wild price swings.

In the event of a reduction in value of the collateral asset (ETH), Maker liquidates CDPs and auctions off the ETH inside for DAI until there is enough DAI to pay back what was extracted from the CDP. So far, so good...

What happens though, if the price of ETH crashes well below the one-to-one collateralization ratio in a very short time-frame. This is where MKR - the native token of the ecosystem - comes in. MKR is an ERC-20 that has governance rights over the Maker smart contracts. As mentioned in a previous version of the newsletter, the governance rights granted to MKR holders, preside over state; put simply, holders of MKR have influence over the key risk parameters of the system in a way that materially changes the composition of the system (state). These include:

The Debt Ceiling - maximum amount of debt that can be created by a single type of CDP

The Liquidation Ratio - ration between collateral and debt

The Stability Fee - an annual percentage yield and needs to be paid by the CDP user

The Penalty Ratio - the max amount of Dai raised from a Liquidation Auction

Incentivization to participate in the governance of the platform as a MKR holder, materializes in stability fees. The more collateral in the system, and the more DAI is issued, the higher the value of those fees. As it becomes apparent, governance rights are valuable in the Maker ecosystem. We'll dig deeper into exactly how much tomorrow.

Part 2

Today, we continue with the dive on Maker from where we left off - governance on the platform vis a vis the MKR token. The way governance materializes, is via proposals instigated by different members of the community (which is largely organizing in the Maker DAO subreddit), that are voted for by staking the MKR token. Voting power is equivalent to the amount of MKR at stake.

The voting process for the governance is done through continuous approval voting. In simple terms, any MKR holder can vote for any number of proposals with the MKR that they they hold. They can also submit a new proposal or cast or withdraw their vote any time they want. The proposal with the maximum votes from MKR holders becomes the top proposal and can be activated to implement any changes in MakerDAO.

The incentives interplay for MKR holders and governance participants is two-fold (at least on a high-level); participating to earn the stability fee, but also participating to ensure that the platform is well functioning so that the long term value of the investment (MKR) is more likely to increase.

This is an interesting relationship, as often the governors will be called to sacrifice short term gains (less stability fee) for a longer term payoff (MKR price appreciation). Under the MakerDAO system, stability fees are denominated in DAI but must be paid in MKR. Once paid, the MKR is burned, reducing the supply and hypothetically increasing the price of MKR. Reducing stability fees means that less MKR is burnt, potentially decreasing the price of MKR. We actually such a turn of events play out many a times in 2018, with the latest event recorded in December. Governance requires constant involvement, in order to ensure that it is always a representative number of votes changing the state of the system, and not the other way around.

As you can imagine, when such critical decisions are at - well - stake, consensus via a widely disparate demos can be hard to achieve, and maybe in fact not optimal in the long run - this is an opinion espoused by Rune Christensen, founder of the Maker DAO platform, in a recent edition of the Unchained podcast. Thus far, the constitution of MKR holders seems to be highly concentrated, mitigating that risk on the one hand, but on the other leaving a large amount of decision making power to the Polychains and a16z's of the world.

Santiment recently ran an analysis of the on-chain Maker DAO network and uncovered that there is indeed a high level of concentration in address interactions. While most ERC-20 contract activity is distributed as in the Santiment Network's case, in Maker the network of interacting addresses is a lot more tightly knit.

Another property that describes the governors, and arguably favours relative centralization, is their function as the buyer of last resort. Should the collateral in the system not be enough to cover the amount of Dai in existence, MKR is created and sold onto the open market in order to raise the additional collateral, providing a strong incentive for MKR holders to responsibly regulate the parameters at which CDPs can create Dai, as it will ultimately be their money on the line should the system fail. As such, deep governor pockets act more as a feature, rather than a bug.

In order to prevent system failures (e.g. a 51% attack or a sharp drop in the price of the collateral asset), Maker attempts to mitigate the risk in two ways; (i) a delay mechanism and (ii) a global settlement mechanism.

The delay mechanism kicks in after a vote is completed, in which time window stakeholders can audit the new code for 24 hours. If the code is reviewed and considered detrimental to the system, then the system will be shut down before it can be deployed.

Now in the event of a black swan event that critically threatens the system, Maker DAO initiates global settlement; a process through which the entire system freezes and all holders of DAI and CDPs are returned the underlying collateral. Global settlement can be triggered by a select group of trusted individuals who hold the global settlement keys. The collateral owners are at that point exposed to whatever market volatility ensues, but are nonetheless guaranteed return of their collateral, after which point the system reboots.

If an attacker bought 51% of the active MKR stake, and somehow tried to corrupt the system, the settlers would initiate the global settlement process. After that is complete, the reformed Maker DAO would be spawned and the attackers 51% stake would have been removed, leaving only the honest MKR holders left. Given both the carrot and stick type incentives outlined here, it becomes evident that corrupting the system is very expensive and therefore not an optimal play.

In pt.3, we'll take a look at how DAI keeps its peg, how that is likely to be affected with the introduction of multi-collateral DAI and what the general implications are.

Part 3

As outlined in parts 1 and 2, the way MakerDAO system works is that users pool Ether together (referred to as PETH, or pooled ETH), and after this pooling, the issued DAI tokens are collateralised against this asset-locked reserve. The way DAI maintains its peg against the USD then, is by adjusting the key parameters of the system to incentivize demand and supply forces to bring the peg back to balance. Consider the following example, as outlined by Alex Larssen; as the price of ETH crashed along with the rest of the market back in November 2018, Maker DAO triggered a series of CDP liquidations - a process that involves withdrawing DAI from the market and returning PETH to the CDP holders.

In the period examined, there were 3 main liquidation events, after which the DAI ecosystem found itself in an excess demand condition. As such, the governors brought the stability fee down (cost of creating a CDP) in order to make it more attractive for participants to provide collateral. Subsequently DAI returned to its target range. As you can imagine, in a period of excess supply (such as the current), the governors will strive to increase the stability fee, to part of the market to withdraw collateral and contract the supply of DAI (in fact there is a currently a vote in place to increase the stability fee to 1.5%).

The problem here, as far as stablecoins are concerned, is that there are no evident demand-side ways to keep the peg in place. As Su Zhu and Hasu explored in their recent piece, "Maker Dai: Stable, but not scalable", Maker DAO does not allow a margin for professional arbitrageurs to get involved in exploiting price discrepancies to bring the DAI peg to balance, primarily due to the fact that DAI is not interchangeable with its collateral on a 1:1 ratio. The following passage sheds some light into this;

When market demand pushes the price of DAI to $1.02, you can again take $1.00 USD, buy $1.00 ETH (or any other asset that can be used as collateral) and lock it in a CDP. The problem, however, is that for each $1.00 ETH locked up, Maker will give you less than $1 of Dai. That is due to the requirement for over-collateralization. The current collateralization ratio is 150%, so $1.00 ETH in a CDP can generate up to 0.66 Dai (this ratio could change, but it’s never going to be close to 100%).

While you wait for the price of Dai to drop, you are stuck in an unfortunate position:

1) You don’t know when, or if, the price of Dai will fall again

2)Since you cannot complete all the steps of the cycle simultaneously, you are stuck with long exposure to ETH while you wait. You want to sterilize the risk by shorting ETH, but that incurs an additional borrow cost.

3) You have an additional cost of capital for locking up the part of sterilized ETH you didn’t borrow Dai against, which is at least 33% (since you can draw $0.66 Dai for every $1 ETH). The cost of that is the risk-free rate of USD.

4) There is an additional cost for closing the CDP.

Now here's the catch - according to them (and in fact I have no trouble warming to the idea), Maker DAO is not about the stablecoin! The stablecoin in the model is rather a feature, but not the main value proposition. Instead, that is long leverage and treasury/payroll management for ICOs by generating liquidity on the ETH collected in the fundraise, while acting as a swap of sorts, allowing borrowers to defer capital gains tax to a later date. As Hasu and Su Zhu put it, the general misunderstanding is that the purpose of Maker DAO "is not to create a scalable, censorship-resistant stablecoin. It is to be able to generate censorship resistant stability for anyone holding a volatile censorship resistant asset." From that perspective, short term peg fluctuations don't matter as much, as they do for pure stablecoins such as Tether and USDC, so long as long term stability is guaranteed.

Of course, working on a single collateral model, with the collateral being a highly volatile asset such as ETH, is not exactly catering to future guarantees of stability. The relative unpredictability of the stability fee will persist, as long as ETH volatility persists, erroding the overall value proposition. However, let's not forget that single collateral is only v.1, with v.2 being just around the corner - but that's perhaps a story for tomorrow's edition!

Before we close today's session on Maker DAO, I'd like to highlight an important realization that I feel is generalizable accross a slew of smart contract applications and cryptoassets overall; in their current form, they are tools with a set of properties that loosely define the opportunity space they exist in. In other words, their utility is driven by the narrative around them, as much as the narrative around them is driven by their utility.

Considering that we are talking about pieces of technology that are so new they are often framed by the devs themselves as "experiments", and are built on open standards, it shouldn't be surprising at all that their utility is also open to interpretation.

In fact, this is actually a crucial piece in the process of cryptoassets and open protocols to finding product-market fit, and if anything, it's an extremely powerful feature (cc: hivemind). As these protocols mature, the ratio between narrative and utility should skew towards utility, and the feedback cycles should become shorter as the utility space is more clearly defined.

Sidenote: I saw a tweet recently that really hit the spot; the metric that really matters in DeFI, is the total value of assets locked in those smart contracts - not the DAU. If that is true however, then a follow-on point is also true; UX needs to improve beyond just simple interfaces and short user journeys. For these apps to become sticky, they also need to be able to work in a "set it and forget it" way - consider that Maker DAO, as it stands is a high friction application, that requires CDP holders to monitor the stability fee and act accordingly.

Simple interfaces and short user journeys are great for reeling users in; what happens after users are in, is largely what will decide whether or not these users will stick with the platform, once the novelty wears out.

Part 4

After a short intermission, we continue today with our dive into Maker DAO and today we discuss more recent developments, as well as the impeding multi-collateral DAI and its potential implications. The Maker DAO team released the code for Multi-Collateral Dai back in November 2018 and contracts have been deployed to the Kovan testnet (Ethereum). Through that process, the various contracts have been put to the test, undergoing several iterations. A key - and highly attractive - feature of the Maker DAO Mainnet is the improved UI and UX, with a revamped governance page (already in place) and a new CDP Portal.

Now, in various parts of editions 1-3, we talked about the stability of DAI, and how ETH volatility is major pain point in the process of keeping the DAI stable. Multi-collateral DAI will gradually introduce the ability to collateralize pretty much any asset on the Ethereum blockchain. Now at first glance this seems to me as a double edged sword; on the one hand you are opening up to a multitude of assets, increasing the potential collateral pool and thus amplifying the amount of DAI that can be issued, smoothing out some of the demand side pressures in the stability of DAI. On the other hand however, given that we are still some way off from tokenized T-Bills (on the Ethereum blockchain no less), it seems that by widening the spectrum of tokens you are introducing in the collateral pool, the total volatility that the collateral pool is exposed to, increases as well.

Consider the following plot for example. The volatility (sigma) of the daily returns of a swathe of popular ERC-20's that could be used in the collateral pool, in the year between Oct. 2017 and Oct. 2018, was actually higher than Ethereum's in ALL cases. For specificity, ETH's volatility was at ~0.05, while the average volatility of the basket of tokens (weighed by market cap) stood at ~0.11 - almost double of that in ETH.

Let's then take a look at what would happen as to the total volatility exposure of the collateral pool as we gradually introduce more ERC-20's to the mix.

As you can observe volatility exposure increases by more than 50% once 40% of the basket is composed of ERC-20's. If we approximate the likely final distribution by market caps, it would look more like a 15% ERC-20's in the total pool - which would approximate to a volatility profile of 0.68, or a 20% increase from current levels.

In any case, not insignificant, and to compound that it is unclear how much bandwidth the higher absolute value of the collateral will provide in offsetting the increased volatility effect. At least at a high level, if demand grows in line with supply, and the collateralization ratio remains the same that shouldn't impact the net effect of volatility.

There is an argument here to be made about the unavailability of the ERC-20's that are locked in collateral, helping smooth out volatility and put upwards pressure on the price, due to scarcity, but also, I imagine that the prime candidates for inclusion in the pool, are tokens that are already in cold storage and do not actively participate in the market - inc which case, the net effect is still intact.

However, there is another policy lever introduced in Multi-Collateral DAI (MCD), that will likely help control that increase in volatility; the DAI Savings Rate (DSR). A person who holds DAI can lock and unlock DAI into a DSR contract at any time. Once locked into the DSR contract, DAI continuously accrues, based on a global system variable called the DSR. There are no restrictions or fees for using DSR other than the gas required for locking and unlocking. The DSR is funded out of the Stability Fees paid by CDPs. For example, if the average Stability Fees collected on CDPs is 3%, it could be used to fund a DSR of 2%. The purpose of this feature is to help balance supply and demand of DAI and will be one of the monetary policy levers that decentralized Maker Governance can control.

It is a global parameter that needs to be adjusted often to deal with short-term changes in market conditions of the Dai economy. This is in contrast to Risk Governance, which is a long-term process that involves setting Stability Fees, and other risk parameters individually for each collateral type

This is more or less what we know so far. To avoid overload, I'll opt for a semicolon here and defer the final piece of the Maker DAO dive to Monday, where we'll look into the weaknesses of the model and the various criticisms around it. Till then, enjoy the weekend all!

Part 5

We kick off the week with the final piece of the Maker DAO dive, focusing on the criticism around the system and product. We'll attack the points one-by-one, kicking off with the relative unpredictability of the stability fee.

1) Unpredictable stability fee: As we've explored previously, the stability fee is an annualized figure, paid once a CDP is closed. Once the fees have been collected, the smart contract platform transfers the MKR to a contract called the Burner. As no one has the ability to remove funds from that address, all MKR that is contained there is forever removed from circulation. Given that governance is executed by staking MKR, big holders have more control over the stability fee, thus making the EV of participation in the collateral pool more unpredictable for smaller entities - and thus governance more centralized. This might be a feature, as wider participation might just not be possible as it would ramp up the amount of noise in the decision making process. Participating in governance, as the value of the platform increases, comes with a prerequisite of increasingly higher resource commitment (time & effort).

PSA: @MakerDAO is raising the stability fee to 3.5% per year this week.

— Alex Miller (@crypto_dev_alex) March 4, 2019

Closed my CDP out. Fun while it lasted, but going from 0.5% to 3.5% in a few months is too rich for my blood. Best of luck ✌️

2) Poor off-chain stabilization ability: You can't trade DAI for USD, therefore it becomes difficult for arbitrageurs to participate, as once again the EV is tied to collateral volatility, while the multiple steps necessary to close a CDP introduce a significant amount of friction. Therefore, as on-chain arbitrage is the only way to control stability, Maker DAO faces the same problems as other centralized digital currencies, including counterparty risk, and the risk of getting its accounts frozen or seized and shut down by governments.

3) Maker DAO doesn't scale very well: Given the above, as we have discussed in previous edition, it seems that Maker DAO's ability to scale, is somewhat capped - as its scalability is supply side driven and the responsiveness to demand side movements is somewhat capped by a time-lag. Hasu and Su Zhu did a good job in demonstrating this, so I am borrowing directly from their analysis: "...the combined market cap of all crypto assets listed on coinmarketcap is less than $300 billion. Let’s assume that Maker’s mature version will be able to include CDP types for crypto assets that cover 50% of the crypto market cap, and people want to put 10% of all tokens in CDPs. Then, with a 300% average collateralization they’ll have a maximum Dai market cap of $3.3 billion." Therefore, Maker DAO is more accurately described as a lending facility and less so as a stablecoin issuer.

4) The MKR token could be deemed a security: An often overlooked implication of the incentive structure here, is that the probability that the MKR token is deemed a security is non-trivial. A lot of that will be decided upon the case history that the SEC builds, and the degree to which they think that the pool of participants in the Maker DAO governance is decentralized or not.

5) Low volumes in MKR introduces a liquidity risk: While Maker DAO ranks highly in mcap (~#30), its liquidity profile tells a different story. The lack of trading volume translates into substantial liquidity and systematic risks for MKR holders, as they might incur a substantial loss in transaction value when they liquidate or enter into positions. In some instance, illiquidity could cost investors 20% of the token price, and it is important to note that illiquidity increase during bear markets, which is further exacerbated in a black swan event where MKR is liquidated to cover losses.

6) Short-term multi-collateral DAI: As we have seen in recent communications of the team, the first stage of multi-collateral DAI, will include ERC-20 derivatives of ETH. However, almost all ERC-20s exhibit a higher beta than ETH, implying that stabilization in MCD will be *harder, not easier* when MCD is introduced.

7) General concerns with the role of Oracles in the model: Oracles, in the Maker DAO model, are trusted third parties that provide the system with price feeds. The Maker DAO team, aggregates those feeds through a contracts called the medianizer - more on which can be found here. The system is fairly well thought out, however, be that as ti may, oracles still constitute an attack vector, as they can be corrupted. More on what the team is working on wrt oracles here.

TIL @polychaincap bought 1% of MKR Supply (10,000 MKR) in 2017 for ~$40k in Jan 2017 ($4/MKR). It's currently worth $6.5M.

— Andrew Kang (@Rewkang) March 3, 2019

a16z crypto bought 60,000 MKR ~1.5 years later for $15M ($250/MKR).

Somewhere between those deals, @MakerDAO went from long moonshot to THIS IS HAPPENING

The progress that the Maker DAO ecosystem has been truly remarkable, and in the process it has created millions of USD in value, particularly for its early investors and team. However, as today's section demonstrated, one must be cognizant of the fact that the project is still an early stage foray. A lot remains to be proven, and more certainty in MKR as a potential investment will be enabled once we know more about the MCD upgrade. It appears that at the moment a lot about Maker DAO is in a state of flux, as little is known about the impact of adding ERC-20s to the collateral mix, MKR's legal standing, and the reaction of the marginal CDP holder to price hikes in the stability fee. Hopefully this series provided readers with a good overview of how the model works and the various nuances around it - ultimately building a mental framework, upon which future judgements can be made on.

Beyond the hype on Uniswap

More recently, a lot of metaphorical twitter ink has been spilled over Uniswap, a DEX built on Ethereum, that has no underlying token and has been thus far built on the accord of Hayden Adams, with a couple of small grants from the Ethereum Foundation and balance.io.

It's pretty easy to understand why all this hype around the DEX, as since its launch in November, Uniswap has been recording some impressive growth numbers. Today we'll try to uncover if there is more to the application, than bored ETH whales moving money around, playing with the newest community toy.

Uniswap is an on-chain market maker allowing the swapping of ERC20 tokens, as well as ETH to an ERC20, and vice-versa. It also allows participants to contribute to liquidity pools for any ERC20 token, and gain commissions in the form of exchange fees for doing so. The model looks a lot like the Bancor network, with the main differences being that (i) Uniswap charges no listing fee - Bancor requires staking BNT tokens to create a market, (ii) costs significantly less gas, and (iii) is entirely decentralized and therefore censorship resistant - whereas on Bancor, markets can be frozen.

The removal of all those friction points in the model - compared to Bancor, has lead to Uniswap quickly attracting a non-trivial amount of ETH & DAI liquidity (plot #1 below), while it is increasingly attracting a larger share of the total trades executed on DEXes (plot #2 below).

Uniswap uses thin delegateproxy contracts (similar to eip-1167, but using a different bytecode) for creating new markets, so it's extremely cheap. Market pairs also only exist from ETH-token, which means a token-token pair doesn't need its own market, it just needs the 2 tokens to have an ETH pair.

Another interesting element of the model, is the fact that there is no order book. Instead the trades get settled at an exchange rate provided by a simple equation - x * y = k . k is a constant value that never changes, whereas x and y represent the quantity of ETH and ERC20 tokens available in a particular exchange that ultimately determines the exchange rate. The curve below represents the possible exchange rate outcomes, at a high level.

I'll avoid getting into too much detail about how that works (refer here for more context), but a good takeaway here is that the simplicity of the model, provides a compelling way for *smaller* trades to get executed without any of the order book woes (e.g. liquidity gaps). This post from Ross Bulat on Medium describes the nuances of the model well - including the liquidity pool requirements and the key role of arbitrageurs in keeping the pool balanced.

Now, you might wonder why that's useful at all?! Well, in fact, as Token Analyst uncovered in a recent post, *small* machine to machine transactions (or contract to contract) actually outweight human to machine transactions on the Ethereum blockchain!

Moving forward, as scalability comes to the Web 3.0 stack and along with it meaningful Dapps, we can easily imagine the proportion swinging heavily towards the machine to machine side of the pendulum, with nexuses of smart contracts interacting with one another and millions of micro-transactions taking place daily. In that instance, DEX protocols like Uniswap are likely to unlock their full potential, allowing Dapps to access instant pooled liquidity, without the risk of slippage.

Of course the slippage story is different for larger transactions via Uniswap. According to Ameen Soleimani of Spankchain, with $50K of tokens in reserve for trading, it takes $350 to cause 1% slippage, $2600 for 5%, and $5500 for 10%. Thus the model is inherently limited by the static pricing mechanism, and its utility is limited to smaller transactions. That said, it's not hard to imagine a future where you have a range of different DEX protocols, for varying transaction sizes, and pooled liquidity.

Liquidity of course, will not come for novelty, but rather for profit. As it stands, the liquidity providers on Uniswap are entitled to a 0.3% fee off every swap, on a pro rata basis. This is not the only way one can make a return on liquidity provision. The liquidity provider receives tradable liquidity tokens as a unit of account of what has been committed to Uniswap. These tokens can be subsequently provided as collateral to Maker DAO (or another DeFi application or protocol that has a market for those) in exchange for DAI, which can then be swapped for a PoS token (e.g. ETH 2.0), on which the liquidity provider can earn further revenue. Here's how Uniswap envisions the model.

Pretty neat, huh? Be that as it may, there is a big caveat here and that is that said returns are expressed in ETH terms (or in terms of any other ERC-20 that is offered for liquidity). As such, any price change in the underlying asset (e.g ETH), would cause a reduction in the value of the stake, relative to holding the original assets, in a way that the resulting losses could be greater than the fees received. Effectively, there is no reason for a liquidity provider to participate, except for if they are long ETH. Pintail has demonstrated this very effectively in his study of the net position of account 0xf369af914dBed0aD7afdDdEbc631Ee0FDA1b4891, the very first liquidity provider to the Uniswap smart contract.

Given ETH's price swings, the net position of the liquidity provider has been negative for most of the time since engaging in the contract. At the same time, however, the user has been collecting fees, which implies that were the price of ETH to return to the same level it stood at when the contract was initiated, the user would have collected close to 12% annualised return. The same author, explores how providing liquidity to Uniswap compares to HOLDing ETH for different levels of ETH appreciation.

Interesting; it appears that providing liquidity for Uniswap is more profitable than HODLing for between 100% and 150% appreciation range in the price of ETH, but less profitable beyond that range. For more info on how that result was reached you can refer to the equivalent post here.

There are a few more caveats to consider when assessing Uniswap's value proposition. First, each trading pair requires its own smart contract, so creating new trading pairs and markets could be quite costly and storage intensive. Yes, it only takes an ETH pair to create a new pair out of two ERC-20's (if ETH/ZRX and ETH/DAI exist on the platform, then ZRX/DAI is also possible), but still in considering the whole universe of ERC-20s (>3000), that is a lot of redundant smart contracts to store on a blockchain, that at present, has serious scalability issues.

Another thing to consider is that Uniswap is built entirely on-chain, which means it is more prone to front-running, and thus makes it expensive for market makers who may need to rapidly change strategies. It also means that speed is not part of the value proposition. Finally, Uniswap is provisioned for ERC-20 tokens alone, and has no apparent plans to support ERC-721 or other standards - which of course could change fairly quickly - but as it stands, limits its utility somewhat (thought truth be told, there's Boxswap for 721's, that does a pretty good job at covering that base).

In all, overlooking its limitations, it becomes fairly evident why Uniswap has managed to attract so much interest recently and with it, a fair amount of traction; an interesting model, with a simple UI/UX (see below), that managed to get off the ground with nothing but talent and a couple of grants. No ICO, no venture investment, no native token, no fanfare and big promises. In absence of all this baggage, it has managed to get adoption on the fly and put a compelling use case to front and centre of the small, but dynamic DeFi universe. But above all, it has driven home what is a valuable lesson that many have chosen to forget; underpromise & overdeliver.