Your Custom Text Here

A model at odds; reviewing Brave’s token economics

Takeaways

Brave is a standout among crypto projects from the ICO era, when considering the adoption it has managed to drive.

The MAU numbers are still low, when compared to other browser products.

BAT, the native protocol asset, only finds utility as a payment token, which dampens Braves adoptability.

While the adoption numbers are encouraging, more users doesn't necessarily translate into more ad spend, as Brave's core value proposition is ad-blocking.

The ads shown on Brave Rewards are mostly of poor quality and still very crypto specific. Better quality ads and better payouts to users (currently $0.5 pcm) will improve adoption.

Brave is one of the breakout crypto-friendly products to come out of the 2017 ICO boom. The browser is a privacy-first product, offshoot of Mozilla Firefox and fork of Chromium, powered by a cryptoeconomic layer in the back end. Instead of a traditional advertising model, Brave shares 70% of the ad revenue generated, with users, in the form of Basic Attention Tokens (BAT). Whether a user is exposed to ads or not, is up to the their discretion.

Adoption

Recently, the browser surpassed 8M MAU, a YoY growth rate of 166%. While the absolute figures pale compared to Chrome's 3B users, they are certainly outstanding in a crypto context. If the assumption that internet users across the world will increasingly keep becoming privacy sensitive holds true, then a window of opportunity opens up for Brave. On the browser end, Brave is faster than Chrome, while its integration with Duckduckgo on the search engine layer, boosts its privacy preserving value proposition.

Whether or not Brave is an attractive investable opportunity through BAT, largely depends on BAT's token economics. BAT is the native network token that is primarily used as a payment token, in the exchange for attention between advertisers and users. While an ad-blocking browser by default, in Brave users are presented with the option to share their data with advertisers, and see ads in exchange for BAT.

1.5B tokens were issued and distributed over 85% to investors and the wider market - a big long term positive in my book. Until further notice, there will never be any inflation - also a big net positive. BAT tokens have no further intended utility than the payment function described above - a feature I perceive as a net negative.

The numbers of publishers signing up to the Brave ecosystem are steadily increasing. The more publishers there are on the platform, the more attention there is on the platform and thus the more attractive it will be for advertisers to use Brave instead of competing ad networks. In order to do that, advertisers will be required to build up BAT reserves to pay users with.

Over the long term, advertisers would have to engage in some form of reserve management on their BAT holdings, in order to lock down a best price in terms of USD, and optimize their cost basis.

The model is already getting some traction, most of which comes from the crypto-native community. The quality of ads that Brave shows is relatively low, with the majority of the advertised brands being VPN and exchange products. Unsurprising - given the type of user that has become an early Brave adopter, but for the product to become stickier, I feel we would have to see better quality advertising.

Brave token economics from the ground-up

Earlier on, I mentioned that I see BAT's utility as * only * a payment token, as a net negative. The reason why, is that it introduces a lot of overhead for advertisers. There is virtually no reason for merchants to adopt a highly unstable currency equivalent as means of payment in order to reach audiences, except perhaps for if they are long the platform itself - in which case the presumption becomes that every merchant will wear an investor hat. Even then, the case for pure payment tokens is grim as the aforementioned adoption mechanism is a zero-sum game.

If the majority of token economy participants decide to just build up reserves of the native payment token, you would have to assume that their involvement in the Brave ecosystem will not drive the majority of their business, so long as running costs cannot be covered using said token without exchanging it for fiat. In itself, that limits the addressable market.

Now, if the majority of participants decide to not be exposed to volatility and sell down on their token denominated income immediately upon receiving it, then everybody else is incentivised to do so - or be left holding the bag. If we agree that this dynamic is true, then it creates the perfect conditions for a race to the bottom.

The final argument that could work in Brave's favour, would be that the product will be so irresistible and as such attract so many users, that it will be impossible for advertisers to ignore it.

This could be the case for Brave, only it can't, as long as its core value proposition is - quite literally - blocking ads.

I have been using Brave with the Rewards feature on for 3 months now as an experiment and earned 5.9 BAT thus far, which amount to $0.5 pcm at current prices. In western world standards this is inconsequential. Personally, I would rather pay 3x as much to not have to bear with ads.

It’s neither stable, nor volatile - what is it?

For almost 2 years now, BAT's price has ranged between $0.15 and $0.50, and while that makes a good case for relative stability enforced by market forces, it certainly is not as good as a stablecoin's, while it doesn't seem to have the potential for a moonshot either.

Given this PA history, one would expect those advertisers that decide to build BAT reserves to drive up the price to ~$0.5, at which point cyclical sellers would be triggered and they would drive the price down again. Conversely, at prices near the $0.15 level, utility seekers would start buying up reserves again. Without a systematic mechanism to break the cycle, I could see it just endlessly repeating. Good for the speculator that is interested in taking advantage of that cyclicality, but bad for almost everyone else.

A better model would be one predicated on some sort of stablecoin, where BAT would be the protocol asset that would give validators that would stake it access to ledger fess. We are increasingly seeing traction in the work token space, with Terra's dual token model providing for a good example. More on that, in a future post.

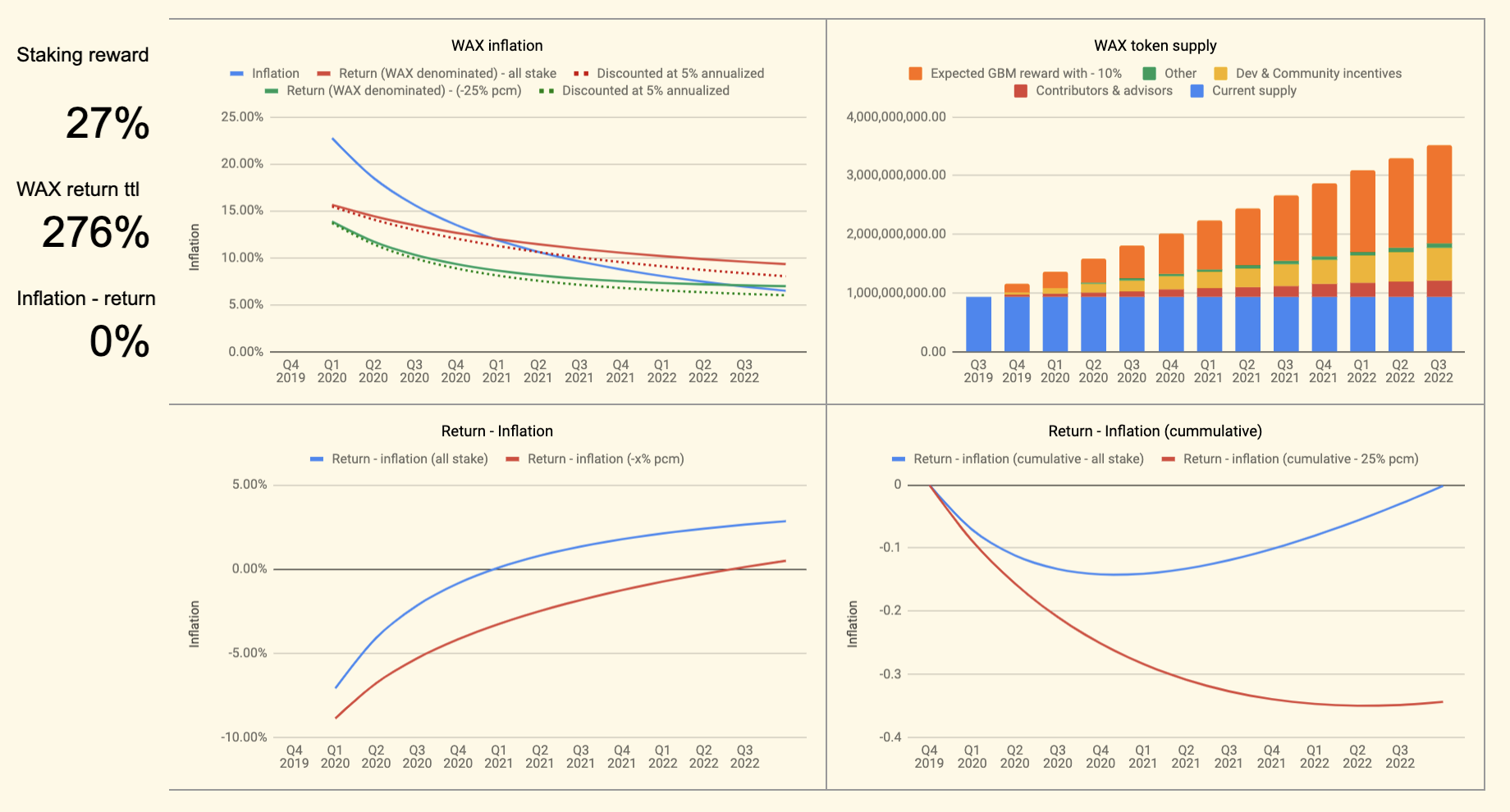

Modelling out the WAX mainnet token economy offering

The present report has been put together drawing from two editions of Decentral Park’s internal daily newsletter, and is presented in format similar to the original (Part 1 & 2). The key findings here are:

WAX will double its notional total supply upon mainnet launch. This is a notional 50% dilution of current holders.

Current holders will have the opportunity to maintain their pro-rata share, only if they remain staked for 3-years - they will receive 1/1092 of their total staked holding every day for those 3 years. Should Genesis Block program (GBM) participants unstake at any point, they lose claim to the remaining residual value stream, and that stream is burned.

Given that the available staking return outside the GBM is roughly 1%, one should consider committing for the whole 3 years of staking, IF and only IF they expect the demand for WAX to increase in excess of the supply of WAX tokens by ~ $130M, over the course of 3 years.

WAX currently owns a large proportion of the total supply. Given that their incentives to remain staked (e.g. lower opportunity cost) are higher than most other parties, they are highly likely to end up with a higher pro-rata share of the network/tokens, at the end of 3-years.

Further, they will initially run 20/21 Block Producers, earning the majority of the inflationary rewards - until they hand over to other interested parties. That further puts WAX in an advantageous position over their token holders - except for if they waive all rewards that accrue from producing blocks.

Please remember that while the model that powered this report is not perfect (e.g. doesn’t make a clear distinction between circulating and non-circulating supply - and probably misses a few more nuances), it is very useful in uncovering different scenaria, and setting benchmarks with respect to the value of the WAX token in the next 3-4 years.

What we know:

- current available supply: 942,732,360 WAX

- total supply: 1,850,000,000 WAX

- total supply will be raised to 3,700,000 WAX by 2022 - a 2x increase

- the additional total supply will be distributed as Genesis Block Rewards (GBM)- a drip function that doubles your holdings in WAX in 3 years (you receive 1/1092 every day), so long as you keep your holdings staked.

- the staking rewards outside that, are speculated to be 1% annualized

If you read between the lines, what WAX is saying is that they will be diluting everybody by 50% over three years, unless they commit to staking all their holdings - and still be subject to some dilution via inflation.

Let's see what modelling with these parameters looks like;

So, should one keep their WAX bonded for 3 years, they should receive 105% their initial WAX back. However, when accounting for inflation, the effective return is -66%, assuming that no new demand hits WAX post Mainnet (edge case).

The curve becomes much steeper when assuming that the staker unbonds 20% of their holdings every month (green line). In other words, the system is designed to keep you locked-in for the whole 3 years.

In order to "break even" under these conditions, one would need a 27% staking yield (annualized) - which is categorically out of the question.

Indicatively, in order to keep the token price at current levels, given the amount of inflation currently planned, WAX would have to 4x its marketcap over three years.

That is add another $180M to its marketcap (1% of the current crypto mcap). However, given that the digital items trading space is projected to be worth somewhere between $20B and $50B, this is not unlikely.

What else we know:

- if you don't participate in GBM upon mainnet launch, you don't get to participate in it ever (happens automatically as you send ERC-20's to burn address).

- as you unstake from the GBM allocation, you cannot re-stake and the remainder of that allocation that would be earmarked for issuance is burned.

What this means is that if we don't see demand for the platform front-run the Mainnet launch to secure allocations for access to the WAX blockchain (which should lead to a nice price bump), every unit of demand that comes to WAX post-Mainnet launch, effectively decreases the inflation rate - as stakers that don't need real estate on WAX (e.g. exchanges or WAX itself), pass their Mainnet tokens on to the incoming demand. As these tokens are unbonded, the earmarked future issuance is burned.

Now, with that in mind, let's have a look at how this plays out, when incorporating these parameters into the model - initially assuming a 10% growth in demand for WAX tokens (as a proxy from demand for real estate on the WAX Mainnet) per quarter.

The growth in all examples that follow, is benchmarked off of $1M initial (new) demand for WAX tokens, starting from Q4 2019.

It seems that with a 10% demand growth, the net improvement is only 4%. Not ideal.

Let's see what happens when you increase the growth projection to 30% per quarter.

Much improved, however, when adjusted for inflation the net return is still negative.

With a little more experimenting, we get to a break-even growth figure of 38.2% per quarter. That translates to approximately $130M of fresh monies hitting the WAX token economy over the course of 3-years.

Beyond that point, things get really interesting. The output for 45% growth per quarter (or ~$200M over the 3 years) points to a 61% inflation adjusted return for the staker. I've also included a positive projection, with the assumption that $2M of new demand hits WAX post Mainnet, with that demand figure growing at 30% per quarter.

The inversion of the "Expected GBM reward" schedule when accounting for demand, should lead to material price appreciation.

Concluding remarks

If the output of the model is correct, then one should consider committing for the whole 3 years of staking, IF and only IF they expect the demand for WAX to increase by ~ $130M over the course of 3 years. Again, considering that the digital items industry is worth $20B to $50B, this is not unlikely at all.

If on the other hand, that kind of confidence in WAX's future performance is not there, then the numbers point to the fact that the potential staker should pack up for greener pastures.

As it stands the holding base of WAX is highly centralized, and so if the thesis about demand seeping through to the platform post Mainnet launch is correct, then things should play out somewhere in the range outlined above.

Part 2

When Part 1 was drafted, the 1% staking reward was taken as anecdotal speculation. Part 2 revisits some of the elements explored in Part 1, accounting for additional information shared by WAX - among which, confirmation that the staking return is likely to range between 0.5% and 1%. Why? Well because staking returns are distributed among stakers (roughly) as follows:

staking return = (tokens staked/total tokens staked) * voting engagement scoreThe voting engagement score ranges between 0 and 1 and to be as close to 1 as possible, you have to be engaged in voting for guilds (delegates) on a weekly basis. As outlined in Part 1, the 1% return is not nearly enough to provide a potential staker with satisfactory enough incentives to stick with it for the long-run. With that variable now known, what the model implies is, in fact, that for the staker to break even, the new demand for WAX token, in excess of current equilibrium, would have to start at approx. $1.15M in Q4 of 2019 and grow at ~40% every quarter from that point onwards.

All things considered though, simple staking is not the only way to earn rewards. If the holder believes that the excess demand condition outlined above and in Part 1is likely to transpire, it would make sense to increase their engagement by either running a Guild (Block Producer), OR at least funding one, so that they ultimately increase the magnitude of the residual return we might be entitled to.

The team recently announced that Hyperchain Capital will be running 1/21 Guilds. The remaining 20 will be run by WAX and a company called StrongBlock.

I find that somewhat concerning. Part 1 concluded that WAX currently owns a large part of the already existing supply of WAX tokens. With them being the residual claimants of the vast majority of the inflationary rewards (at least for the launch and post-genesis periods) only compounds the effect and net-net attributes to WAX being diluted less than all other holders, effectively increasing their share of the token economy.

What is also outstanding in the above statement, is that it implies that the time when WAX decides to relinquish control, is 100% their call (as we gradually roll out), and potentially still a work in progress.

Further, another inconsistency found, was that while WAX quotes the annual inflation figure to be 5%, given that the total supply will double in 3 years after Mainnet launch, the effective inflation rate starts closer to 25%. If this is a perpetuity of 5% added on top of that initial 25%, then the dilution the passive investor would be facing, would be even steeper[1].

Even with the new batch of information on the table, it appears that there is still more pending. More particularly WAX has hinted to "transfer agents" and the "WAX Marketplace" as other ways to earn WAX tokens, more on which will be released in the coming weeks. Within the latest comms from the team, there is also a mention of an additional way to earn WAX tokens at Mainnet launch.

Concluding remarks

If this was the private market, WAX’s strategy would make sense - dilute your earlier investors and ask them to top up on their investment to maintain their percentage of ownership (for those that don’t have any pro-rata clauses at least). In the private markets however, when the time to raise the next round would come (the Genesis Block Program looks very much like a next round for WAX), the valuation of the company would stand at ~2x to 3x the previous rounds. On the contrary, WAX’s current valuation stands at ~1x that of the previous rounds, while token holders have already been diluted by approximately 40%. Consider the following:

June 22nd, 2018:

WAX Mcap: $72M

Token price: $0.113

May 26th, 2019:

WAX Mcap: $72M

Token price: $0.077

That’s a 40% hit on the token price, caused by the new WAX tokens entering circulation. Given all of the above, there is little to point towards the trend reversing here, and the market seems to have caught wind of that. Since the WAX team started drip feeding information about the upcoming Mainnet release, the token price seems to not have responded favourably (yet). One would expect demand to materialize, as investors would rush to secure their Genesis Block Program spots - alas, to no avail, amounting to an affirmation of the concerns raised throughout Parts 1 & 2 of the report.

Token value accrual models; the good, the bad and the ugly

It happens again and again - in 2017, amidst the monumental bull run, it was commonplace for crypto pundits to exalt the properties of various token models. Most of you that were around in that time, will remember.

Conversely, now that prices have collapsed, often the very same pundits have been quick to switch sides, and bang the "tokens are worthless" drum.

It seems fairly obvious to me that there is a lot of System 1 thinking at play here - most likely attributable to a mix of anchoring and bandwagon effects, and a positive feedback loop between price action and sentiment.

While many criticisms of token models have value, I suspect that we cannot come to conclusive arguments about value accrual just yet - only speculation. But also, until we have a suite of repeatable business and token models (like we do in the off-chain world), it is unlikely that we'll get to see what lies on the other end of the inflexion point in the adoption curve.

So, before we move on, cheers to the unsung heroes that are experimenting with all kinds of different models in honesty and good faith; without them, we will probably never find the pot of gold at the end of the rainbow.

Now, given that we have a lot more information about what works and what doesn't compared to a couple of years ago, it's worth recapping how the different narratives on token value accrual have developed over time.

For reference, I am borrowing the classification below from Fabric Ventures to help frame the discussion.

After multiple boom and bust cycles, this is what I feel we know collectively about value capture in token economies. This is by no means conclusive, but rather a crutch in navigating a noisy landscape. If you have any thoughts on the classifications above, I'd love to hear them.

If this appears to be too small, you can access the table here too.

At this point I wanted to note a few things, regarding the learnings we can take from this; (i) hybrid models seem like they have a lot of potential - combining properties artfully only widens the potential SAM, as a token can be different things to different stakeholders , (ii) taxi-medallion-like access tokens are the flavour du jour when it comes to narratives, but it might just hold ground, (iii) utility-come-payment tokens are dead in the water, as they introduce hurdles to adoption and that (iv) the jury is very much still out on governance tokens.

Statefulness and value capture

One of the themes that has really stuck with me from the past couple of weeks on the road, is the idea that "tokens that govern state will accrue value, while tokens that govern schema won't". Here, I am looking to unpack this argument, touching on topics of statefulness vs statelessness, governance and value sinks. We'll start by understanding what statefulness is in a software context.

Stateless vs Stateful

State is the bulk of information referring to preceding events or user interactions, stored in a protocol (or programme) from t=0 up to t=n. A computer program stores data in variables, which represent storage locations in the computer's memory. The content of these memory locations, at any given point in the program's execution, is called the program's state.

By extension then, a stateless protocol does not require the server to retain session information or status about each communicating partner for the duration of multiple requests. Examples include the Internet Protocol (IP), which is the foundation for the Internet, and the Hypertext Transfer Protocol (HTTP). Conversely, a program is described as stateful if it is designed to remember preceding events or user interactions. In stateful protocols, information about previous data characters or packets received is stored in variables and used to affect the processing of the current character or packet.

Statelessness imbues software with fast performance, reliability, and the ability to grow, by re-using components that can be managed and updated without affecting the system as a whole, even while it is running. In contrast stateful protocols, provide continuity and are more intuitive (since state related data are embedded).

Statefulness and value over time

Blockchains and smart contracts platforms, are in their majority, stateful. By definition, a blockchain is a database of past states - such that the further away we move from t=0, the more stateful it becomes. This is equally true for Web 2.0 systems, but especially true for blockchains.

Consider the following example: a user may interact with the service to address a personal need, for example, to find a certain website with the aid of a keyword query. The service satisfies that need by returning a list of results, but a byproduct of the user’s action is the service improving its global state - e.g. with every new search queried, Google's algorithm is more informed than before, and therefore better able to deliver optimal results for all future users.

So it appears that while code is of paramount importance to kickstart a software system, as time goes by, the value migrates from the code to the state captured by the programme/protocol. A service’s reliance on state makes it fundamentally different than a tool. A service’s software, when instantiated, creates a vessel for persistent state. It starts off empty and becomes useful only when filled with data, users or both. State compounds and becomes more valuable exponentially. Code, while crucial for the stable operation and evolution of a service, becomes less important and necessary to defend.

As Denis Nazarov of a16z has noted in the recent past, "blockchains are too slow to do any computing that is really interesting aside from their one redeeming feature: they maintain “state” incredibly well", while concluding that they are probably the best “state machine” invented to date — properly aligning the incentives to coordinate a network of machines distributed globally that maintain this state of truth without an intermediary.

Statefulness and value capture

So, from the above, it follows that (i) stateful protocols have memory; the more memory they accumulate, the more valuable they become and (ii) value migrates from code to state over time. At the same time, (iii) the more memory stateful protocols and apps accumulate, the slower they become and (iv) blockchains are the best state machines invented to date.

Granted all of the above then, is there truth to the statement - "tokens that govern state will be valuable, tokens that govern schema won't"?

Since blockchains are in effect databases, we can define schema as the overall design of the database - the skeleton structure that represents the logical view of the entire database. It tells how the data is organized and how the relations among them are associated. Conversely, as mentioned previously, state refers to the content of a database at a moment in time.

It then follows that as governance of an open source system comes into place, the value accrues increasingly more to the ability to influence future state. In other words, having influence over the terms that influence state (e.g. Maker DAO liquidation margins) is more valuable relatively to having influence over how those terms come into effect.

The king is naked

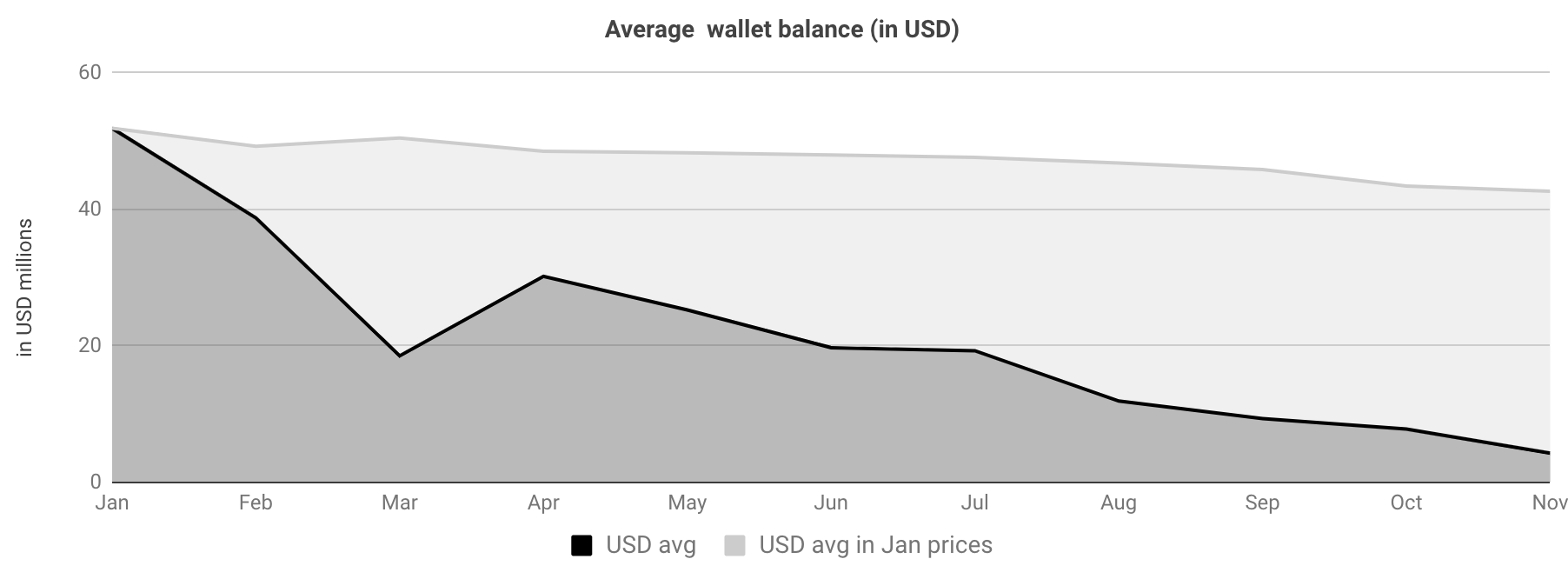

The Diar has recently published some data on the treasury balances of ~100 crypto projects' ICO wallets, and I thought it would be interesting to run a few analyses on the data and see what sort of insights (if any) we can elicit. Before we dive in, it's useful to note that the projects examined here only represent 5-10% of the whole. There is a multitude of other projects that are not included in this dataset - or any other publicly available dataset as far as I know. If you happen to know of a more comprehensive resource, do get in touch. Now without further ado, let's get to it;

The first figure shows the total ETH balances in the projects' wallets and how that figure has been shaped over the course of the year. The total wallet balance has decreased by 17.8%, while ETH's price has decreased by ~90% from January 2018. Putting two and two together, this amounts to a 92% decrease in the USD value of those holdings. In absolute terms, the average project's treasury, lost about $38M in potential value held, since January - see figure below.

Theis is a summary of the simple average size of a random project's treasury, accross 2018, expressed in USD terms. The dark area represents the actual value of the treasury, while the light shaded area, represents the value lost due to ETH's price depreciation. In order to highlight the degree of potential mismanagement, let's run a quick thought experiment; starting out in January 2018, project ABC has $55M in its treasury. Let's also assume that the optimal budget distribution for ABC, looks something like what's presented below.

The above implies that ABC can hire approximately 60 professionals (engineers, ops, marketing), at Silicon Valley salaries (~$180k a year average), and keep them employed for 3 years. While I don't have concrete numbers on this, last time I checked, most projects that raised in 2017 are not on a hiring spree of that magnitude. Let's further assume that ABC actually consumed 17.8% of the $55M they raised (approx. $10M), out of which $5M is committed towards payroll (by the above assumptions). With that they hired 9 people, which sounds about right. Now, had they managed their finances optimally, they would still have enough money to hire another 50 people to help them build and ship. What the reality points to is that they can actually hire about 3 more people at SV salaries and keep them employed for 3 years. That's a tentative loss of 47 high quality professionals. Wow! Surely there was no CFO among those 9 hires that ABC went ahead with in 2018...Note that we are talking about are technology organizations that have raised money to deliver a product/network - not finance shops. As such I don't see how they can justify being long ETH.

Now let's have a quick look at how the total ETH liquidation activity relates to the price of ETH.

The correlations here are not very revealing; there is a positive 30% correlation (relatively weak) between this month's ETH liquidation and next month's %D in the price of ETH and a negative 40% correlation between this month's ETH liquidation and this month's %D in the price of ETH . In other words, there is some correlation between projects selling ETH and the price of ETH dropping, but it seems to not be the most compelling reason why. Again, we are only tracking ~5% of all projects here, so there is a chance that the correlations would increase if we had a more complete picture.

To round off the analysis, let's take a look at how specific projects have managed their treasuries thus far.

The dark area signifies how much the project's treasury was worth in USD terms in January, while the the light area represents the % of the treasury that the project consumed (or liquidated to USD). There are a few key observations here; (i) the distribution between total value in January and amount consumed is random, (ii) the amount consumed has not impacted price overall (for most projects) - one would assume that better management would translate to the market pricing that in and (iii) some of the most hyped projects, like Tezos and Golem, have consumed none of their ETH holdings in 2018.

There are a few conclusions that really stand out here; (i) the average project has no idea how to or low interest in managing their treasury and part of that lack of activity is most likely owing to the fact that (ii) in 2017 projects raised way too much money, compared to what they needed to ship product. It would also appear that (iii) many of the teams succumbed to the whims of an anchoring bias, and while the USD value of their ETH holdings 2-5xed over the course of 2017, they didn't bother to liquidate some, as that was way over the amount that they initially asked for. Of course, this is something that we already knew, but interesting to see how it has played out over time. This abundance of (notional) capital, surely did not create an optimal incentive structure for the teams.

As the industry matures, the need for diverse skillsets is evident, as is the current lack of design and ops/finance people in crypto - despite the increasing flow. While there are many things wrong with the "real world" that crypto has the potential to improve, there are equally many things done right, that crypto would be better off adopting.