Your Custom Text Here

Beyond the hype on Maker DAO

Part 1

For the next few editions I'm going to dig into DeFi's most prized asset - Maker DAO. Being cognizant of time limitations here, I'll break this up into multiple pieces - which will hopefully make it a little bit more digestible for all. Maker has conjured up a lot of excitement among the community and for good reason, as at the moment around 2% of all the ETH in circulation is locked up in the Maker smart contract.

What exactly is Maker though? In short, Maker is a set of smart contracts responsible for the issuance of the DAI stablecoin (pegged to the dollar). DAI is backed by Ether that is locked into the Maker smart contract as collateral - see below for a glimpse of the UI.

As an ETH holder, you can lock up your ETH as collateral and issue an equivalent amount of DAI. This function is known as a “collateralized debt position” or CDP. Due to the volatility of ETH, the amount that needs to be provided as collateral is a multiple of a 1:1 relationship, to prevent positions being liquidated on wild price swings.

In the event of a reduction in value of the collateral asset (ETH), Maker liquidates CDPs and auctions off the ETH inside for DAI until there is enough DAI to pay back what was extracted from the CDP. So far, so good...

What happens though, if the price of ETH crashes well below the one-to-one collateralization ratio in a very short time-frame. This is where MKR - the native token of the ecosystem - comes in. MKR is an ERC-20 that has governance rights over the Maker smart contracts. As mentioned in a previous version of the newsletter, the governance rights granted to MKR holders, preside over state; put simply, holders of MKR have influence over the key risk parameters of the system in a way that materially changes the composition of the system (state). These include:

The Debt Ceiling - maximum amount of debt that can be created by a single type of CDP

The Liquidation Ratio - ration between collateral and debt

The Stability Fee - an annual percentage yield and needs to be paid by the CDP user

The Penalty Ratio - the max amount of Dai raised from a Liquidation Auction

Incentivization to participate in the governance of the platform as a MKR holder, materializes in stability fees. The more collateral in the system, and the more DAI is issued, the higher the value of those fees. As it becomes apparent, governance rights are valuable in the Maker ecosystem. We'll dig deeper into exactly how much tomorrow.

Part 2

Today, we continue with the dive on Maker from where we left off - governance on the platform vis a vis the MKR token. The way governance materializes, is via proposals instigated by different members of the community (which is largely organizing in the Maker DAO subreddit), that are voted for by staking the MKR token. Voting power is equivalent to the amount of MKR at stake.

The voting process for the governance is done through continuous approval voting. In simple terms, any MKR holder can vote for any number of proposals with the MKR that they they hold. They can also submit a new proposal or cast or withdraw their vote any time they want. The proposal with the maximum votes from MKR holders becomes the top proposal and can be activated to implement any changes in MakerDAO.

The incentives interplay for MKR holders and governance participants is two-fold (at least on a high-level); participating to earn the stability fee, but also participating to ensure that the platform is well functioning so that the long term value of the investment (MKR) is more likely to increase.

This is an interesting relationship, as often the governors will be called to sacrifice short term gains (less stability fee) for a longer term payoff (MKR price appreciation). Under the MakerDAO system, stability fees are denominated in DAI but must be paid in MKR. Once paid, the MKR is burned, reducing the supply and hypothetically increasing the price of MKR. Reducing stability fees means that less MKR is burnt, potentially decreasing the price of MKR. We actually such a turn of events play out many a times in 2018, with the latest event recorded in December. Governance requires constant involvement, in order to ensure that it is always a representative number of votes changing the state of the system, and not the other way around.

As you can imagine, when such critical decisions are at - well - stake, consensus via a widely disparate demos can be hard to achieve, and maybe in fact not optimal in the long run - this is an opinion espoused by Rune Christensen, founder of the Maker DAO platform, in a recent edition of the Unchained podcast. Thus far, the constitution of MKR holders seems to be highly concentrated, mitigating that risk on the one hand, but on the other leaving a large amount of decision making power to the Polychains and a16z's of the world.

Santiment recently ran an analysis of the on-chain Maker DAO network and uncovered that there is indeed a high level of concentration in address interactions. While most ERC-20 contract activity is distributed as in the Santiment Network's case, in Maker the network of interacting addresses is a lot more tightly knit.

Another property that describes the governors, and arguably favours relative centralization, is their function as the buyer of last resort. Should the collateral in the system not be enough to cover the amount of Dai in existence, MKR is created and sold onto the open market in order to raise the additional collateral, providing a strong incentive for MKR holders to responsibly regulate the parameters at which CDPs can create Dai, as it will ultimately be their money on the line should the system fail. As such, deep governor pockets act more as a feature, rather than a bug.

In order to prevent system failures (e.g. a 51% attack or a sharp drop in the price of the collateral asset), Maker attempts to mitigate the risk in two ways; (i) a delay mechanism and (ii) a global settlement mechanism.

The delay mechanism kicks in after a vote is completed, in which time window stakeholders can audit the new code for 24 hours. If the code is reviewed and considered detrimental to the system, then the system will be shut down before it can be deployed.

Now in the event of a black swan event that critically threatens the system, Maker DAO initiates global settlement; a process through which the entire system freezes and all holders of DAI and CDPs are returned the underlying collateral. Global settlement can be triggered by a select group of trusted individuals who hold the global settlement keys. The collateral owners are at that point exposed to whatever market volatility ensues, but are nonetheless guaranteed return of their collateral, after which point the system reboots.

If an attacker bought 51% of the active MKR stake, and somehow tried to corrupt the system, the settlers would initiate the global settlement process. After that is complete, the reformed Maker DAO would be spawned and the attackers 51% stake would have been removed, leaving only the honest MKR holders left. Given both the carrot and stick type incentives outlined here, it becomes evident that corrupting the system is very expensive and therefore not an optimal play.

In pt.3, we'll take a look at how DAI keeps its peg, how that is likely to be affected with the introduction of multi-collateral DAI and what the general implications are.

Part 3

As outlined in parts 1 and 2, the way MakerDAO system works is that users pool Ether together (referred to as PETH, or pooled ETH), and after this pooling, the issued DAI tokens are collateralised against this asset-locked reserve. The way DAI maintains its peg against the USD then, is by adjusting the key parameters of the system to incentivize demand and supply forces to bring the peg back to balance. Consider the following example, as outlined by Alex Larssen; as the price of ETH crashed along with the rest of the market back in November 2018, Maker DAO triggered a series of CDP liquidations - a process that involves withdrawing DAI from the market and returning PETH to the CDP holders.

In the period examined, there were 3 main liquidation events, after which the DAI ecosystem found itself in an excess demand condition. As such, the governors brought the stability fee down (cost of creating a CDP) in order to make it more attractive for participants to provide collateral. Subsequently DAI returned to its target range. As you can imagine, in a period of excess supply (such as the current), the governors will strive to increase the stability fee, to part of the market to withdraw collateral and contract the supply of DAI (in fact there is a currently a vote in place to increase the stability fee to 1.5%).

The problem here, as far as stablecoins are concerned, is that there are no evident demand-side ways to keep the peg in place. As Su Zhu and Hasu explored in their recent piece, "Maker Dai: Stable, but not scalable", Maker DAO does not allow a margin for professional arbitrageurs to get involved in exploiting price discrepancies to bring the DAI peg to balance, primarily due to the fact that DAI is not interchangeable with its collateral on a 1:1 ratio. The following passage sheds some light into this;

When market demand pushes the price of DAI to $1.02, you can again take $1.00 USD, buy $1.00 ETH (or any other asset that can be used as collateral) and lock it in a CDP. The problem, however, is that for each $1.00 ETH locked up, Maker will give you less than $1 of Dai. That is due to the requirement for over-collateralization. The current collateralization ratio is 150%, so $1.00 ETH in a CDP can generate up to 0.66 Dai (this ratio could change, but it’s never going to be close to 100%).

While you wait for the price of Dai to drop, you are stuck in an unfortunate position:

1) You don’t know when, or if, the price of Dai will fall again

2)Since you cannot complete all the steps of the cycle simultaneously, you are stuck with long exposure to ETH while you wait. You want to sterilize the risk by shorting ETH, but that incurs an additional borrow cost.

3) You have an additional cost of capital for locking up the part of sterilized ETH you didn’t borrow Dai against, which is at least 33% (since you can draw $0.66 Dai for every $1 ETH). The cost of that is the risk-free rate of USD.

4) There is an additional cost for closing the CDP.

Now here's the catch - according to them (and in fact I have no trouble warming to the idea), Maker DAO is not about the stablecoin! The stablecoin in the model is rather a feature, but not the main value proposition. Instead, that is long leverage and treasury/payroll management for ICOs by generating liquidity on the ETH collected in the fundraise, while acting as a swap of sorts, allowing borrowers to defer capital gains tax to a later date. As Hasu and Su Zhu put it, the general misunderstanding is that the purpose of Maker DAO "is not to create a scalable, censorship-resistant stablecoin. It is to be able to generate censorship resistant stability for anyone holding a volatile censorship resistant asset." From that perspective, short term peg fluctuations don't matter as much, as they do for pure stablecoins such as Tether and USDC, so long as long term stability is guaranteed.

Of course, working on a single collateral model, with the collateral being a highly volatile asset such as ETH, is not exactly catering to future guarantees of stability. The relative unpredictability of the stability fee will persist, as long as ETH volatility persists, erroding the overall value proposition. However, let's not forget that single collateral is only v.1, with v.2 being just around the corner - but that's perhaps a story for tomorrow's edition!

Before we close today's session on Maker DAO, I'd like to highlight an important realization that I feel is generalizable accross a slew of smart contract applications and cryptoassets overall; in their current form, they are tools with a set of properties that loosely define the opportunity space they exist in. In other words, their utility is driven by the narrative around them, as much as the narrative around them is driven by their utility.

Considering that we are talking about pieces of technology that are so new they are often framed by the devs themselves as "experiments", and are built on open standards, it shouldn't be surprising at all that their utility is also open to interpretation.

In fact, this is actually a crucial piece in the process of cryptoassets and open protocols to finding product-market fit, and if anything, it's an extremely powerful feature (cc: hivemind). As these protocols mature, the ratio between narrative and utility should skew towards utility, and the feedback cycles should become shorter as the utility space is more clearly defined.

Sidenote: I saw a tweet recently that really hit the spot; the metric that really matters in DeFI, is the total value of assets locked in those smart contracts - not the DAU. If that is true however, then a follow-on point is also true; UX needs to improve beyond just simple interfaces and short user journeys. For these apps to become sticky, they also need to be able to work in a "set it and forget it" way - consider that Maker DAO, as it stands is a high friction application, that requires CDP holders to monitor the stability fee and act accordingly.

Simple interfaces and short user journeys are great for reeling users in; what happens after users are in, is largely what will decide whether or not these users will stick with the platform, once the novelty wears out.

Part 4

After a short intermission, we continue today with our dive into Maker DAO and today we discuss more recent developments, as well as the impeding multi-collateral DAI and its potential implications. The Maker DAO team released the code for Multi-Collateral Dai back in November 2018 and contracts have been deployed to the Kovan testnet (Ethereum). Through that process, the various contracts have been put to the test, undergoing several iterations. A key - and highly attractive - feature of the Maker DAO Mainnet is the improved UI and UX, with a revamped governance page (already in place) and a new CDP Portal.

Now, in various parts of editions 1-3, we talked about the stability of DAI, and how ETH volatility is major pain point in the process of keeping the DAI stable. Multi-collateral DAI will gradually introduce the ability to collateralize pretty much any asset on the Ethereum blockchain. Now at first glance this seems to me as a double edged sword; on the one hand you are opening up to a multitude of assets, increasing the potential collateral pool and thus amplifying the amount of DAI that can be issued, smoothing out some of the demand side pressures in the stability of DAI. On the other hand however, given that we are still some way off from tokenized T-Bills (on the Ethereum blockchain no less), it seems that by widening the spectrum of tokens you are introducing in the collateral pool, the total volatility that the collateral pool is exposed to, increases as well.

Consider the following plot for example. The volatility (sigma) of the daily returns of a swathe of popular ERC-20's that could be used in the collateral pool, in the year between Oct. 2017 and Oct. 2018, was actually higher than Ethereum's in ALL cases. For specificity, ETH's volatility was at ~0.05, while the average volatility of the basket of tokens (weighed by market cap) stood at ~0.11 - almost double of that in ETH.

Let's then take a look at what would happen as to the total volatility exposure of the collateral pool as we gradually introduce more ERC-20's to the mix.

As you can observe volatility exposure increases by more than 50% once 40% of the basket is composed of ERC-20's. If we approximate the likely final distribution by market caps, it would look more like a 15% ERC-20's in the total pool - which would approximate to a volatility profile of 0.68, or a 20% increase from current levels.

In any case, not insignificant, and to compound that it is unclear how much bandwidth the higher absolute value of the collateral will provide in offsetting the increased volatility effect. At least at a high level, if demand grows in line with supply, and the collateralization ratio remains the same that shouldn't impact the net effect of volatility.

There is an argument here to be made about the unavailability of the ERC-20's that are locked in collateral, helping smooth out volatility and put upwards pressure on the price, due to scarcity, but also, I imagine that the prime candidates for inclusion in the pool, are tokens that are already in cold storage and do not actively participate in the market - inc which case, the net effect is still intact.

However, there is another policy lever introduced in Multi-Collateral DAI (MCD), that will likely help control that increase in volatility; the DAI Savings Rate (DSR). A person who holds DAI can lock and unlock DAI into a DSR contract at any time. Once locked into the DSR contract, DAI continuously accrues, based on a global system variable called the DSR. There are no restrictions or fees for using DSR other than the gas required for locking and unlocking. The DSR is funded out of the Stability Fees paid by CDPs. For example, if the average Stability Fees collected on CDPs is 3%, it could be used to fund a DSR of 2%. The purpose of this feature is to help balance supply and demand of DAI and will be one of the monetary policy levers that decentralized Maker Governance can control.

It is a global parameter that needs to be adjusted often to deal with short-term changes in market conditions of the Dai economy. This is in contrast to Risk Governance, which is a long-term process that involves setting Stability Fees, and other risk parameters individually for each collateral type

This is more or less what we know so far. To avoid overload, I'll opt for a semicolon here and defer the final piece of the Maker DAO dive to Monday, where we'll look into the weaknesses of the model and the various criticisms around it. Till then, enjoy the weekend all!

Part 5

We kick off the week with the final piece of the Maker DAO dive, focusing on the criticism around the system and product. We'll attack the points one-by-one, kicking off with the relative unpredictability of the stability fee.

1) Unpredictable stability fee: As we've explored previously, the stability fee is an annualized figure, paid once a CDP is closed. Once the fees have been collected, the smart contract platform transfers the MKR to a contract called the Burner. As no one has the ability to remove funds from that address, all MKR that is contained there is forever removed from circulation. Given that governance is executed by staking MKR, big holders have more control over the stability fee, thus making the EV of participation in the collateral pool more unpredictable for smaller entities - and thus governance more centralized. This might be a feature, as wider participation might just not be possible as it would ramp up the amount of noise in the decision making process. Participating in governance, as the value of the platform increases, comes with a prerequisite of increasingly higher resource commitment (time & effort).

PSA: @MakerDAO is raising the stability fee to 3.5% per year this week.

— Alex Miller (@crypto_dev_alex) March 4, 2019

Closed my CDP out. Fun while it lasted, but going from 0.5% to 3.5% in a few months is too rich for my blood. Best of luck ✌️

2) Poor off-chain stabilization ability: You can't trade DAI for USD, therefore it becomes difficult for arbitrageurs to participate, as once again the EV is tied to collateral volatility, while the multiple steps necessary to close a CDP introduce a significant amount of friction. Therefore, as on-chain arbitrage is the only way to control stability, Maker DAO faces the same problems as other centralized digital currencies, including counterparty risk, and the risk of getting its accounts frozen or seized and shut down by governments.

3) Maker DAO doesn't scale very well: Given the above, as we have discussed in previous edition, it seems that Maker DAO's ability to scale, is somewhat capped - as its scalability is supply side driven and the responsiveness to demand side movements is somewhat capped by a time-lag. Hasu and Su Zhu did a good job in demonstrating this, so I am borrowing directly from their analysis: "...the combined market cap of all crypto assets listed on coinmarketcap is less than $300 billion. Let’s assume that Maker’s mature version will be able to include CDP types for crypto assets that cover 50% of the crypto market cap, and people want to put 10% of all tokens in CDPs. Then, with a 300% average collateralization they’ll have a maximum Dai market cap of $3.3 billion." Therefore, Maker DAO is more accurately described as a lending facility and less so as a stablecoin issuer.

4) The MKR token could be deemed a security: An often overlooked implication of the incentive structure here, is that the probability that the MKR token is deemed a security is non-trivial. A lot of that will be decided upon the case history that the SEC builds, and the degree to which they think that the pool of participants in the Maker DAO governance is decentralized or not.

5) Low volumes in MKR introduces a liquidity risk: While Maker DAO ranks highly in mcap (~#30), its liquidity profile tells a different story. The lack of trading volume translates into substantial liquidity and systematic risks for MKR holders, as they might incur a substantial loss in transaction value when they liquidate or enter into positions. In some instance, illiquidity could cost investors 20% of the token price, and it is important to note that illiquidity increase during bear markets, which is further exacerbated in a black swan event where MKR is liquidated to cover losses.

6) Short-term multi-collateral DAI: As we have seen in recent communications of the team, the first stage of multi-collateral DAI, will include ERC-20 derivatives of ETH. However, almost all ERC-20s exhibit a higher beta than ETH, implying that stabilization in MCD will be *harder, not easier* when MCD is introduced.

7) General concerns with the role of Oracles in the model: Oracles, in the Maker DAO model, are trusted third parties that provide the system with price feeds. The Maker DAO team, aggregates those feeds through a contracts called the medianizer - more on which can be found here. The system is fairly well thought out, however, be that as ti may, oracles still constitute an attack vector, as they can be corrupted. More on what the team is working on wrt oracles here.

TIL @polychaincap bought 1% of MKR Supply (10,000 MKR) in 2017 for ~$40k in Jan 2017 ($4/MKR). It's currently worth $6.5M.

— Andrew Kang (@Rewkang) March 3, 2019

a16z crypto bought 60,000 MKR ~1.5 years later for $15M ($250/MKR).

Somewhere between those deals, @MakerDAO went from long moonshot to THIS IS HAPPENING

The progress that the Maker DAO ecosystem has been truly remarkable, and in the process it has created millions of USD in value, particularly for its early investors and team. However, as today's section demonstrated, one must be cognizant of the fact that the project is still an early stage foray. A lot remains to be proven, and more certainty in MKR as a potential investment will be enabled once we know more about the MCD upgrade. It appears that at the moment a lot about Maker DAO is in a state of flux, as little is known about the impact of adding ERC-20s to the collateral mix, MKR's legal standing, and the reaction of the marginal CDP holder to price hikes in the stability fee. Hopefully this series provided readers with a good overview of how the model works and the various nuances around it - ultimately building a mental framework, upon which future judgements can be made on.

Beyond the hype on Uniswap

More recently, a lot of metaphorical twitter ink has been spilled over Uniswap, a DEX built on Ethereum, that has no underlying token and has been thus far built on the accord of Hayden Adams, with a couple of small grants from the Ethereum Foundation and balance.io.

It's pretty easy to understand why all this hype around the DEX, as since its launch in November, Uniswap has been recording some impressive growth numbers. Today we'll try to uncover if there is more to the application, than bored ETH whales moving money around, playing with the newest community toy.

Uniswap is an on-chain market maker allowing the swapping of ERC20 tokens, as well as ETH to an ERC20, and vice-versa. It also allows participants to contribute to liquidity pools for any ERC20 token, and gain commissions in the form of exchange fees for doing so. The model looks a lot like the Bancor network, with the main differences being that (i) Uniswap charges no listing fee - Bancor requires staking BNT tokens to create a market, (ii) costs significantly less gas, and (iii) is entirely decentralized and therefore censorship resistant - whereas on Bancor, markets can be frozen.

The removal of all those friction points in the model - compared to Bancor, has lead to Uniswap quickly attracting a non-trivial amount of ETH & DAI liquidity (plot #1 below), while it is increasingly attracting a larger share of the total trades executed on DEXes (plot #2 below).

Uniswap uses thin delegateproxy contracts (similar to eip-1167, but using a different bytecode) for creating new markets, so it's extremely cheap. Market pairs also only exist from ETH-token, which means a token-token pair doesn't need its own market, it just needs the 2 tokens to have an ETH pair.

Another interesting element of the model, is the fact that there is no order book. Instead the trades get settled at an exchange rate provided by a simple equation - x * y = k . k is a constant value that never changes, whereas x and y represent the quantity of ETH and ERC20 tokens available in a particular exchange that ultimately determines the exchange rate. The curve below represents the possible exchange rate outcomes, at a high level.

I'll avoid getting into too much detail about how that works (refer here for more context), but a good takeaway here is that the simplicity of the model, provides a compelling way for *smaller* trades to get executed without any of the order book woes (e.g. liquidity gaps). This post from Ross Bulat on Medium describes the nuances of the model well - including the liquidity pool requirements and the key role of arbitrageurs in keeping the pool balanced.

Now, you might wonder why that's useful at all?! Well, in fact, as Token Analyst uncovered in a recent post, *small* machine to machine transactions (or contract to contract) actually outweight human to machine transactions on the Ethereum blockchain!

Moving forward, as scalability comes to the Web 3.0 stack and along with it meaningful Dapps, we can easily imagine the proportion swinging heavily towards the machine to machine side of the pendulum, with nexuses of smart contracts interacting with one another and millions of micro-transactions taking place daily. In that instance, DEX protocols like Uniswap are likely to unlock their full potential, allowing Dapps to access instant pooled liquidity, without the risk of slippage.

Of course the slippage story is different for larger transactions via Uniswap. According to Ameen Soleimani of Spankchain, with $50K of tokens in reserve for trading, it takes $350 to cause 1% slippage, $2600 for 5%, and $5500 for 10%. Thus the model is inherently limited by the static pricing mechanism, and its utility is limited to smaller transactions. That said, it's not hard to imagine a future where you have a range of different DEX protocols, for varying transaction sizes, and pooled liquidity.

Liquidity of course, will not come for novelty, but rather for profit. As it stands, the liquidity providers on Uniswap are entitled to a 0.3% fee off every swap, on a pro rata basis. This is not the only way one can make a return on liquidity provision. The liquidity provider receives tradable liquidity tokens as a unit of account of what has been committed to Uniswap. These tokens can be subsequently provided as collateral to Maker DAO (or another DeFi application or protocol that has a market for those) in exchange for DAI, which can then be swapped for a PoS token (e.g. ETH 2.0), on which the liquidity provider can earn further revenue. Here's how Uniswap envisions the model.

Pretty neat, huh? Be that as it may, there is a big caveat here and that is that said returns are expressed in ETH terms (or in terms of any other ERC-20 that is offered for liquidity). As such, any price change in the underlying asset (e.g ETH), would cause a reduction in the value of the stake, relative to holding the original assets, in a way that the resulting losses could be greater than the fees received. Effectively, there is no reason for a liquidity provider to participate, except for if they are long ETH. Pintail has demonstrated this very effectively in his study of the net position of account 0xf369af914dBed0aD7afdDdEbc631Ee0FDA1b4891, the very first liquidity provider to the Uniswap smart contract.

Given ETH's price swings, the net position of the liquidity provider has been negative for most of the time since engaging in the contract. At the same time, however, the user has been collecting fees, which implies that were the price of ETH to return to the same level it stood at when the contract was initiated, the user would have collected close to 12% annualised return. The same author, explores how providing liquidity to Uniswap compares to HOLDing ETH for different levels of ETH appreciation.

Interesting; it appears that providing liquidity for Uniswap is more profitable than HODLing for between 100% and 150% appreciation range in the price of ETH, but less profitable beyond that range. For more info on how that result was reached you can refer to the equivalent post here.

There are a few more caveats to consider when assessing Uniswap's value proposition. First, each trading pair requires its own smart contract, so creating new trading pairs and markets could be quite costly and storage intensive. Yes, it only takes an ETH pair to create a new pair out of two ERC-20's (if ETH/ZRX and ETH/DAI exist on the platform, then ZRX/DAI is also possible), but still in considering the whole universe of ERC-20s (>3000), that is a lot of redundant smart contracts to store on a blockchain, that at present, has serious scalability issues.

Another thing to consider is that Uniswap is built entirely on-chain, which means it is more prone to front-running, and thus makes it expensive for market makers who may need to rapidly change strategies. It also means that speed is not part of the value proposition. Finally, Uniswap is provisioned for ERC-20 tokens alone, and has no apparent plans to support ERC-721 or other standards - which of course could change fairly quickly - but as it stands, limits its utility somewhat (thought truth be told, there's Boxswap for 721's, that does a pretty good job at covering that base).

In all, overlooking its limitations, it becomes fairly evident why Uniswap has managed to attract so much interest recently and with it, a fair amount of traction; an interesting model, with a simple UI/UX (see below), that managed to get off the ground with nothing but talent and a couple of grants. No ICO, no venture investment, no native token, no fanfare and big promises. In absence of all this baggage, it has managed to get adoption on the fly and put a compelling use case to front and centre of the small, but dynamic DeFi universe. But above all, it has driven home what is a valuable lesson that many have chosen to forget; underpromise & overdeliver.

Token value accrual models; the good, the bad and the ugly

It happens again and again - in 2017, amidst the monumental bull run, it was commonplace for crypto pundits to exalt the properties of various token models. Most of you that were around in that time, will remember.

Conversely, now that prices have collapsed, often the very same pundits have been quick to switch sides, and bang the "tokens are worthless" drum.

It seems fairly obvious to me that there is a lot of System 1 thinking at play here - most likely attributable to a mix of anchoring and bandwagon effects, and a positive feedback loop between price action and sentiment.

While many criticisms of token models have value, I suspect that we cannot come to conclusive arguments about value accrual just yet - only speculation. But also, until we have a suite of repeatable business and token models (like we do in the off-chain world), it is unlikely that we'll get to see what lies on the other end of the inflexion point in the adoption curve.

So, before we move on, cheers to the unsung heroes that are experimenting with all kinds of different models in honesty and good faith; without them, we will probably never find the pot of gold at the end of the rainbow.

Now, given that we have a lot more information about what works and what doesn't compared to a couple of years ago, it's worth recapping how the different narratives on token value accrual have developed over time.

For reference, I am borrowing the classification below from Fabric Ventures to help frame the discussion.

After multiple boom and bust cycles, this is what I feel we know collectively about value capture in token economies. This is by no means conclusive, but rather a crutch in navigating a noisy landscape. If you have any thoughts on the classifications above, I'd love to hear them.

If this appears to be too small, you can access the table here too.

At this point I wanted to note a few things, regarding the learnings we can take from this; (i) hybrid models seem like they have a lot of potential - combining properties artfully only widens the potential SAM, as a token can be different things to different stakeholders , (ii) taxi-medallion-like access tokens are the flavour du jour when it comes to narratives, but it might just hold ground, (iii) utility-come-payment tokens are dead in the water, as they introduce hurdles to adoption and that (iv) the jury is very much still out on governance tokens.

Statefulness and value capture

One of the themes that has really stuck with me from the past couple of weeks on the road, is the idea that "tokens that govern state will accrue value, while tokens that govern schema won't". Here, I am looking to unpack this argument, touching on topics of statefulness vs statelessness, governance and value sinks. We'll start by understanding what statefulness is in a software context.

Stateless vs Stateful

State is the bulk of information referring to preceding events or user interactions, stored in a protocol (or programme) from t=0 up to t=n. A computer program stores data in variables, which represent storage locations in the computer's memory. The content of these memory locations, at any given point in the program's execution, is called the program's state.

By extension then, a stateless protocol does not require the server to retain session information or status about each communicating partner for the duration of multiple requests. Examples include the Internet Protocol (IP), which is the foundation for the Internet, and the Hypertext Transfer Protocol (HTTP). Conversely, a program is described as stateful if it is designed to remember preceding events or user interactions. In stateful protocols, information about previous data characters or packets received is stored in variables and used to affect the processing of the current character or packet.

Statelessness imbues software with fast performance, reliability, and the ability to grow, by re-using components that can be managed and updated without affecting the system as a whole, even while it is running. In contrast stateful protocols, provide continuity and are more intuitive (since state related data are embedded).

Statefulness and value over time

Blockchains and smart contracts platforms, are in their majority, stateful. By definition, a blockchain is a database of past states - such that the further away we move from t=0, the more stateful it becomes. This is equally true for Web 2.0 systems, but especially true for blockchains.

Consider the following example: a user may interact with the service to address a personal need, for example, to find a certain website with the aid of a keyword query. The service satisfies that need by returning a list of results, but a byproduct of the user’s action is the service improving its global state - e.g. with every new search queried, Google's algorithm is more informed than before, and therefore better able to deliver optimal results for all future users.

So it appears that while code is of paramount importance to kickstart a software system, as time goes by, the value migrates from the code to the state captured by the programme/protocol. A service’s reliance on state makes it fundamentally different than a tool. A service’s software, when instantiated, creates a vessel for persistent state. It starts off empty and becomes useful only when filled with data, users or both. State compounds and becomes more valuable exponentially. Code, while crucial for the stable operation and evolution of a service, becomes less important and necessary to defend.

As Denis Nazarov of a16z has noted in the recent past, "blockchains are too slow to do any computing that is really interesting aside from their one redeeming feature: they maintain “state” incredibly well", while concluding that they are probably the best “state machine” invented to date — properly aligning the incentives to coordinate a network of machines distributed globally that maintain this state of truth without an intermediary.

Statefulness and value capture

So, from the above, it follows that (i) stateful protocols have memory; the more memory they accumulate, the more valuable they become and (ii) value migrates from code to state over time. At the same time, (iii) the more memory stateful protocols and apps accumulate, the slower they become and (iv) blockchains are the best state machines invented to date.

Granted all of the above then, is there truth to the statement - "tokens that govern state will be valuable, tokens that govern schema won't"?

Since blockchains are in effect databases, we can define schema as the overall design of the database - the skeleton structure that represents the logical view of the entire database. It tells how the data is organized and how the relations among them are associated. Conversely, as mentioned previously, state refers to the content of a database at a moment in time.

It then follows that as governance of an open source system comes into place, the value accrues increasingly more to the ability to influence future state. In other words, having influence over the terms that influence state (e.g. Maker DAO liquidation margins) is more valuable relatively to having influence over how those terms come into effect.

A dive into Ethereum's network stats

Taking from Chris Burniske's recent post on crypto fundamentals (especially ETH's) being less depressed in protportion to ETH's USD denominated value, I did some digging on the fundamentals of ETH beyond Gas and hashrate. In today's version of the Daily, I'll present you with some key metrics on Ethereum and attempt to unpack where the state of the network is at present.

Key Takeaways:

The Ethereum network seems to have reached a capacity ceiling in its current form.

Smart contract usage is correlated to relative transaction cost.

ERC-20 is by far the dominant standard.

Poor quality ERC-20's are starting to go offline. That should allow for some network bandwidth to free up.

High quality smart contract useage is accelerating. That is likely to increase the demand for bandwidth - as organic (non-speculative) demand kicks in.

13% of all available ETH is currently locked in Maker DAO. That's an impressive feat, a sign of progress, and a HUGE central point of failure.

Without a scalability solution, the problems that became evident in 2018, will only keep persisting, as adoption of the platform increases.

Exhibit 1: The network has reached a capacity ceiling

These two plots are directly borrowed from Burniske's post and show the relationships between Market cap (Network Value) and daily transactions and hashrate respectively. Safe to make the case that the network holds its relative fundamental strength, despite the price of ETH collapsing. There are a few cases we can make here. The most interesting ones to me are (i) the fact that mania pushed the valuation much higher than the fundamentals, but more interestingly, (ii) the fact that the market is pricing in Ethereum's scalability woes. Plasma is starting to look like a Catch 22, Sharding is being continuously delayed and the Ethereum community has grown bigger than its current organizational structures can accommodate. Be that as it may, the fact that both hashrate and daily transactions have plateaued in 2018, remains. The next couple of graphs show the effects of the network bottleneck, in action.

The two graphs above are representations of smart contract count and the relative transaction cost (measured as Gas value/ETH value). Just a quick glance in enough to reveal that there is an negative correlation between the two constructs. Low relative transaction costs lead to proliferation of smart contracts deployed on Ethereum. Fair. What is positive here is that despite the windfall in ETH's value, we recently hit a local maximum in smart contract count. The flow of developers on Ethereum is increasing - yet, they are likely to find themselves competing for finite resources. Let's take a look on the demand side of those smart contracts.

Exhibit 2: Smart contract usage is correlated to relative transaction cost

The plots above are different permutations of smart contract calls over time. A smart contract call is similar to an API query. As evidenced by the number of unique callers over time, the Gas crisis this past summer (largely attributatble to Fcoin's introduction of trans fee mining), capped the growth of unique callers. Even as transaction costs normalised, the number of unique callers did not return to its previous trajectory. A look at the number of calls might reveal why;

The capacity ceiling in Ethereum's current form becomes evident once more. Call count has plateaued at 300k for pretty much all of 2018. When calls started reaching 400k, transaction fees blew up and the call count returned to the 300k level. The fact that many useless ERC-20s are starting to die out, some capacity should be freed up. Even yet, were this source of demand to be substituted with real users, we can expect that the same mechanics would come into play.

Exhibit 3: ERC-20 is by far the dominant standard

Recently, the number of daily unique ERC-20's in operation took a turn south. The recent drop in the number of ERC-20's coincides with the recent actions from the SEC. Even so, their overall share of the Ethereum network is so large, that makes the traction of other ERC standards (like the NFT - 721) pale in comparison. Still; in relative terms the signs of life in non-fungibles and others are encouraging.

Interestingly, the number of daily transactions of ERC-20's has been on the decrease since July, coinciding with the aforementioned Gas crisis that took place around that time. Part of this change might be attributable to some of the demand sources moving to other platforms and some dying out due to continuously depreciating prices. But there's potentially one more reason...

Exhibit 4: Open Finance Dapps like Maker are starting to get serious traction

The trend change in daily transactions of ERC-20's, as well as the number of smart contract callers, coincides with an acceleration in the trend of increase of the amount of ETH that is stored in the Maker DAO smart contract, held as collateral to issue the DAI stablecoin. At the moment, approximately 13% of the available supply of ETH is locked into that contract (no wonder a16z piled in ~$25M in Maker), while others smart contracts, such as Compound, have started gaining traction (on display in the second graph above).

Concluding remarks

That final point is perhaps what's more encouraging about the ecosystem's development. More is not always better. The evidence that the number of ERC-20s is starting to drop, while high quality smart contracts are accelerating in useage is a highly positive sign, and a trend that we can only hope persists in 2019. However, without a robust scalability solution, the woes of the past are almost certain to keep coming back as demand picks up - and demand from builders for the Ethereum platform shows no signs of slowing down.

Monthly downloads of the Truffle development framework for Smart Contracts

To top that up, the Maker smart contract is increasingly becoming a bigger and bigger bounty for the one to hack it, and a central point of failure for the whole Ethereum ecosystem. Useful to remember that Solidity (Ethereum's programming language) comes without formal verification, and thus higher probability of bugs appearing down the line. So far, so good - but then again it doesn't matter how you fall - what matters is how you land.

The king is naked

The Diar has recently published some data on the treasury balances of ~100 crypto projects' ICO wallets, and I thought it would be interesting to run a few analyses on the data and see what sort of insights (if any) we can elicit. Before we dive in, it's useful to note that the projects examined here only represent 5-10% of the whole. There is a multitude of other projects that are not included in this dataset - or any other publicly available dataset as far as I know. If you happen to know of a more comprehensive resource, do get in touch. Now without further ado, let's get to it;

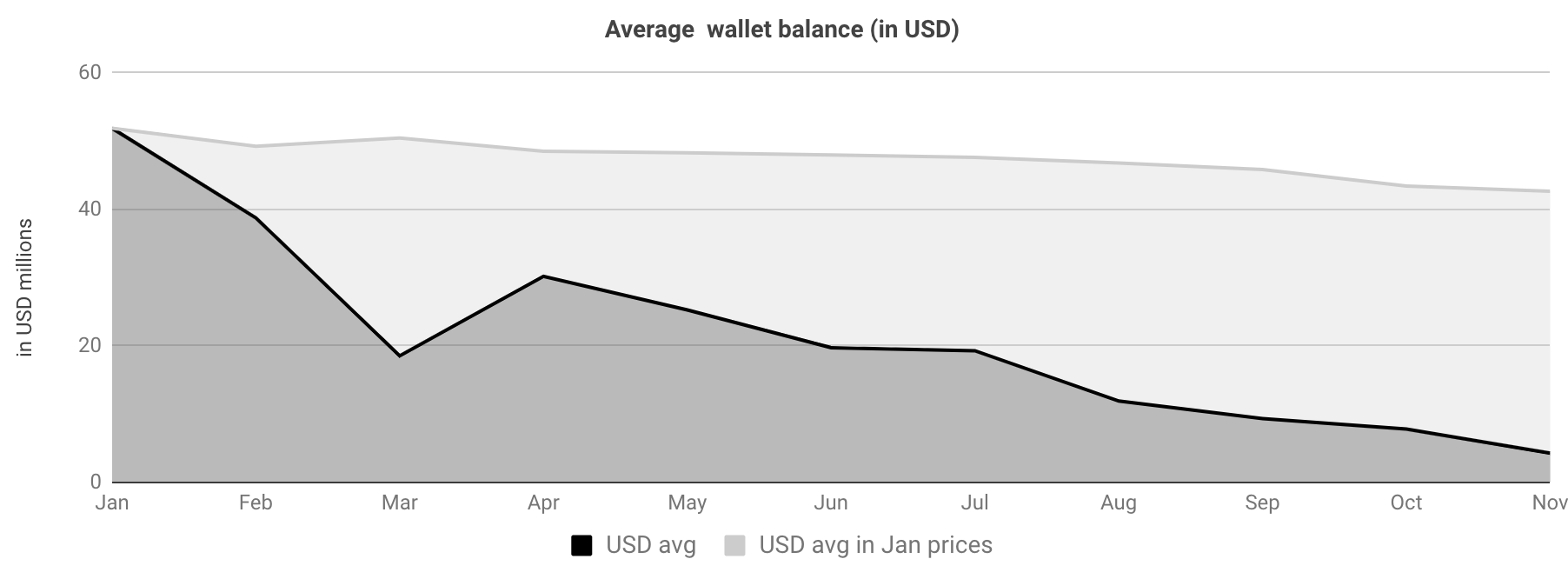

The first figure shows the total ETH balances in the projects' wallets and how that figure has been shaped over the course of the year. The total wallet balance has decreased by 17.8%, while ETH's price has decreased by ~90% from January 2018. Putting two and two together, this amounts to a 92% decrease in the USD value of those holdings. In absolute terms, the average project's treasury, lost about $38M in potential value held, since January - see figure below.

Theis is a summary of the simple average size of a random project's treasury, accross 2018, expressed in USD terms. The dark area represents the actual value of the treasury, while the light shaded area, represents the value lost due to ETH's price depreciation. In order to highlight the degree of potential mismanagement, let's run a quick thought experiment; starting out in January 2018, project ABC has $55M in its treasury. Let's also assume that the optimal budget distribution for ABC, looks something like what's presented below.

The above implies that ABC can hire approximately 60 professionals (engineers, ops, marketing), at Silicon Valley salaries (~$180k a year average), and keep them employed for 3 years. While I don't have concrete numbers on this, last time I checked, most projects that raised in 2017 are not on a hiring spree of that magnitude. Let's further assume that ABC actually consumed 17.8% of the $55M they raised (approx. $10M), out of which $5M is committed towards payroll (by the above assumptions). With that they hired 9 people, which sounds about right. Now, had they managed their finances optimally, they would still have enough money to hire another 50 people to help them build and ship. What the reality points to is that they can actually hire about 3 more people at SV salaries and keep them employed for 3 years. That's a tentative loss of 47 high quality professionals. Wow! Surely there was no CFO among those 9 hires that ABC went ahead with in 2018...Note that we are talking about are technology organizations that have raised money to deliver a product/network - not finance shops. As such I don't see how they can justify being long ETH.

Now let's have a quick look at how the total ETH liquidation activity relates to the price of ETH.

The correlations here are not very revealing; there is a positive 30% correlation (relatively weak) between this month's ETH liquidation and next month's %D in the price of ETH and a negative 40% correlation between this month's ETH liquidation and this month's %D in the price of ETH . In other words, there is some correlation between projects selling ETH and the price of ETH dropping, but it seems to not be the most compelling reason why. Again, we are only tracking ~5% of all projects here, so there is a chance that the correlations would increase if we had a more complete picture.

To round off the analysis, let's take a look at how specific projects have managed their treasuries thus far.

The dark area signifies how much the project's treasury was worth in USD terms in January, while the the light area represents the % of the treasury that the project consumed (or liquidated to USD). There are a few key observations here; (i) the distribution between total value in January and amount consumed is random, (ii) the amount consumed has not impacted price overall (for most projects) - one would assume that better management would translate to the market pricing that in and (iii) some of the most hyped projects, like Tezos and Golem, have consumed none of their ETH holdings in 2018.

There are a few conclusions that really stand out here; (i) the average project has no idea how to or low interest in managing their treasury and part of that lack of activity is most likely owing to the fact that (ii) in 2017 projects raised way too much money, compared to what they needed to ship product. It would also appear that (iii) many of the teams succumbed to the whims of an anchoring bias, and while the USD value of their ETH holdings 2-5xed over the course of 2017, they didn't bother to liquidate some, as that was way over the amount that they initially asked for. Of course, this is something that we already knew, but interesting to see how it has played out over time. This abundance of (notional) capital, surely did not create an optimal incentive structure for the teams.

As the industry matures, the need for diverse skillsets is evident, as is the current lack of design and ops/finance people in crypto - despite the increasing flow. While there are many things wrong with the "real world" that crypto has the potential to improve, there are equally many things done right, that crypto would be better off adopting.

The stablecoin paradox

The more I study emerging stablecoin propositions, the more convinced I become that this is an all-or-nothing market. Unless you have absolute conviction that one design will win, it makes little sense to back any single stablecoin at all.

This isn’t like betting on competing tech platforms where several can coexist. Stablecoins fight for the same narrow space: trust, liquidity, and exchange integration. Every new entrant dilutes the rest, pushing the market toward a single dominant winner.

Stablecoins are also an exceptionally risky business. Beyond the operational fragility of many designs, the value-capture mechanisms that link a stablecoin to its governance token are often murky. Add a hyper-competitive market with almost no barriers to entry, and you have a setup where each new launch erodes the future value of all others. Since early May, when I first started tracking the space, the number of live or planned stablecoins has more than doubled (see stablecoinindex.com for a running list).

This will almost certainly be a winner-takes-most market.

Take the current leader, Tether. Many projects have tried to unseat it, yet none have come close. What’s remarkable is how little effort Tether has made to polish its image—no full audit, constant skepticism—and still, it dominates. Why? First-mover advantage and attention.

Attention converts to revenue. Claiming attention real estate early can make or break a company. Tether might be one implosion away from collapse, but time compounds its advantage: it gets smarter, more entrenched, better resourced.

Now imagine two plausible dethroning scenarios:

Collapse: A revelation shows only 10% of Tether’s supply is actually backed by dollars.

Institutional flood: Tens of billions in institutional capital enter crypto, flowing into the most transparent, regulated alternative.

In either case, the market would reshuffle briefly before a new stablecoin king emerges. The logic mirrors why the world runs on the USD: attention, liquidity, and interoperability. We don’t deal with USD #1 through USD #99. We deal with the USD.

If I had to bet, I’d back the institutionally backed, fully regulated alternative. As the market matures, institutional participants will favor systems that resemble those they already trust. Their adoption would cascade, signaling legitimacy and pulling the rest of the market along.

The arrival of Gemini Dollar and Paxos Standard marks exactly that kind of shift—a sign that crypto is inching toward maturity.

Message from the future: As fate would have it, Circle with USDC would go on and carve its own space in the category.